今回の旅での「迷子・迷宮入り」事件。

みなさんは高速道利用のとき、息抜き・食事でPAやSAを利用されるでしょう。その違いってあんまり自覚もないと思います。一応調べてみると「SAはサービスエリア、PAはパーキングエリアの略。SAは一般的に規模が大きくGSやレストラン施設が充実しているのに対し、PAは規模が小さく駐車場とトイレ中心で、売店やGSは控えめに設置される」とある。注意書きで「SAとPAの明確な区別は難しくPAにもGSがある場合や、SAにレストランやGSがない場合もあり、実際には施設の充実度によって判断するのが一般的」。

ということだそうですが、まぁこのことは漠然と理解はしていた。

ただ「ハイウェイオアシス」となると「SAのもっと大型のもの」程度の認識。正確な概念特定までの必要性も感じていなかった。たぶん多くの人がそうだろうと思います。一応Wiki情報は概要以下。〜高速道路沿いにありSAやPAと一般道路沿いの「道の駅」を複合させたような施設。地域の味覚や物産を購入できる飲食店や売店があるレクリエーション施設というのが特徴。〜

今回の旅の途中、美濃加茂といういい響きの地名を冠したエリアに入線。小腹が空いて、休憩がてら軽食をと思ったのですね。で、SAとハイウェイオアシスの両方があるということだった。

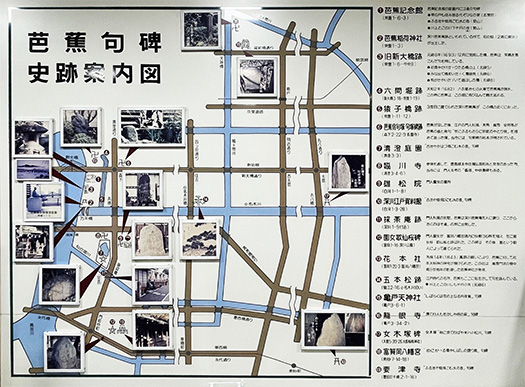

アプローチ道路の⬆地点で「左・ハイウェイオアシス、右SA」という標識がありちょっと迷った後ハイウェイオアシスを選んで左方向にハンドルを切った。そうするとSAから距離が離れていって左奥にハイウェイオアシスとおぼしき建物が見えた。ところがその建物までの道路はフェンスで区切られていて、クルマ進入出来なくなっていた。

そのハイウェイオアシスとおぼしき建物に到達するにははるか手前100mほどの駐車場所に停車して歩いて向かう必要があった。仕切りのフェンスだけが目立っていてそこへの歩行通路もすぐには見通すことが出来なかった。ヘンだとは思ったけれどここまで不親切なら、この先もどうなることか不安が募ったので、やむなく引き返すことに。

で、今度はその車両通路も途中で一方通行・進入禁止なので強制的に急カーブさせられた。「え、マジかよ」であります。ほうほうの体でSAの駐車場に停車して軽食コーナーへ到着。

こちらでも案内が不在で情報がわかる看板なども発見できなかった。やむなく食堂スタッフに事情を聞いてみたが、どうやらフェンスのごく一部に「出入り口」があってそこから歩いてアクセスするとのこと。

ムリそれ、というちょっとワケわかんない体験でした。う〜む。

●お知らせ

拙書「作家と住空間」幻冬舎から電子書籍で発刊

お求めはAmazonで。

https://amzn.asia/d/eUiv9yO

English version⬇

【Highway Oasis and Expressway Service Area: The Lost Child Incident in Minokamo】

Drawn by the place name, what should have been a relaxing break turned into a series of “Hmm…” moments. Minokamo is undoubtedly a nice place, but…

The “Getting Lost/Lost in the Labyrinth” Incident on This Trip.

When using the expressway, you probably stop at PAs or SAs for breaks or meals. I don’t think many people are really aware of the difference between them. Looking it up, it says: “SA stands for Service Area, PA for Parking Area. Generally, SAs are larger with more comprehensive gas stations and restaurant facilities, while PAs are smaller, primarily parking lots with restrooms, and have more modest shops and gas stations.” A note adds: “Distinguishing between SA and PA can be tricky. Some PAs have gas stations, while some SAs lack restaurants or gas stations. In practice, it’s usually judged by the level of facilities available.”

Well, I vaguely understood that much.

However, when it comes to “Highway Oasis,” my understanding was just that it’s “a larger version of an SA.” I never felt the need to pin down the exact concept. I suspect many people feel the same way. Anyway, the Wiki info is below the overview. ~Facilities located along expressways, combining elements of SAs/PAs with the “roadside stations” found along regular roads. Characterized as recreational facilities featuring restaurants and shops where you can purchase local delicacies and products.~

During this trip, I entered an area named Minokamo, which has a nice ring to it. Feeling a bit peckish, I thought I’d grab a light snack while taking a break. It turned out there was both a SA and a Highway Oasis there.

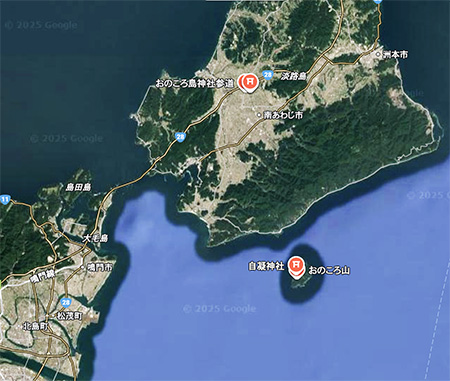

At the ⬆ point on the approach road, a sign said “Left: Highway Oasis, Right: SA.” After a moment’s hesitation, I chose the Highway Oasis and turned left. As I drove away from the SA, I spotted what looked like the Highway Oasis building far off to the left. However, the road leading to it was blocked off by a fence, preventing vehicle access.

To reach that building resembling the Highway Oasis, I had to park in a lot about 100 meters away and walk the rest of the way. Only the dividing fence stood out prominently, and the pedestrian path to it wasn’t immediately visible. I thought it was odd, but if they were this unhelpful already, I grew anxious about what lay ahead. Reluctantly, I turned back.

Then, on the vehicle access road, I was forced into a sharp curve midway due to a one-way/no entry sign. “Seriously?” I thought. Barely managing, I parked in the SA lot and reached the snack corner.

Here too, there was no one to guide us, and I couldn’t find any signs with information. I had no choice but to ask the cafeteria staff about the situation. Apparently, there was a tiny “entrance/exit” in a very small part of the fence, and you had to walk through that to access it.

It was a bit of a baffling experience, like, “No way, that’s impossible.” Hmm.

●Notice

My book “Writers and Living Spaces” published as an e-book by Gentosha.

Available on Amazon.

Posted on 9月 7th, 2025 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 未分類 | No Comments »