日本書紀の記述では、葦原の中つ国の支配権をヤマト王権が確立する過程は紆余曲折を辿り、出雲王権の大国主は最終的に鹿島の祭神・武甕槌大神(たけいかずちおおかみ)の遠征軍によって「国譲り」したことになっている。上の絵は越の国・新潟の弥彦神社に奉納されたものとされる。弥彦神社は同じ日本海文化圏であり、参拝の仕方も出雲と同じく2礼4拍手2礼という形式なので出雲と深く関係するいわば「同族意識」を高く持っていたと思える。出雲としては「不本意だけれど」国譲りということ自体は「正統な」手順を踏んでいたのだとして、その情報が越の国とその民にも伝えられて、この絵のように「了承を求める」と象徴化されたか。

一方のこちらは香取神宮の境内に掲げられていた「国譲り」縁起を表現した絵。香取の神も鹿島神と同行して出雲の殻の「国譲り」に加勢していたとされている。絵の画面上に樹影が写っているのは、日射の影響なのでご容赦ください。香取神宮の祭神・経津主大神(ふつぬしのおおかみ)とともに勝者として出雲の大国主から武の象徴としての剣を捧げられるポーズを取っている。独特の武装放棄表現と見ることができる。

というような神話の世界から日本という国はスタートしている。先日古代ローマのことも触れたけれど、国家というものの正統性という意味では背骨に当たる部分でしょう。国家の正統性にはいろいろな側面・意味合いがあるでしょうが、少なくともこういう説話が説得力を持っていること自体が強い正統性根拠だと思う。

このヤマト王権の正統性の起点で、東国の神は国家統合の武の象徴として登場している。

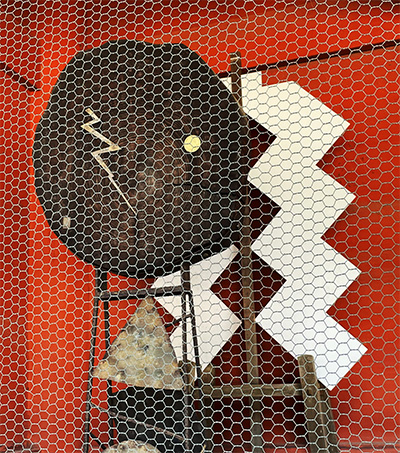

また鹿島神宮の桜門の左右には、写真のような武甕槌大神の紋章のような雷をシンボライズした神具がいわば「鎮守」具として飾られている。やはり「武神」的な色合いを強く感じさせてくれる。

明治以前に「神宮」の称号を与えられていたのは伊勢、香取、鹿島のみというわが国屈指の名社。このような国譲り神話での関係性からすると、関東地域というのはきわめて特殊な位置を占めていることになる。

さてこういう非常に重要な役割を果たした軍神、武の象徴を思わせる存在であるのに、その後の日本史上ではしばらくの間、関東は主舞台ではなく、むしろヤマト王権は繰り返しヤマトタケルという鎮撫軍を東国に派遣している。

地形的には香取の海や霞ヶ浦、鹿島灘などの水郷地帯に位置しているので、田畑という農業経済発展は難しい地域の武神であるので、日本史上ではながく関東開発は遅滞し、その神々の一統は象徴的権威ということに留まっていたものだろうか。王権から国譲りの武功に即して関東の支配権は移譲されたけれど、統治には至って不似合いな存在であったのか。地形的にバラバラの国土で集権的権力構造を作りにくかったのか?結局は独立農業主たちの乱立による無政府的な争乱が常態化していたのだろう。

その後の日本史で、関東には武士による支配構造が確立して、王朝国家とは別の農場開発主たちによる独立した武権を基盤とする国家が成立していく。歴史で解明されているこれ以降の関東の姿と、この鹿島神宮の武神には、どんな関係性があるのかないのか、戸惑い続けております。

English version⬇

Takemikazuchi no Mikami of Kashima, Izumo, and the Yamato Royalty: Exploring the Three Shrines of Eastern Japan-2

The deity Takemikazuchi of Kashima was the greatest contributor to the ceding of the kingdom, yet after that, the Kanto region remained immature in terms of power until the rise of the samurai. Did he fail to manage the economy? …

According to the account in Nihonshoki, the process of establishing the Yamato kingdom as the dominant power in the Land of Reed Plains took many twists and turns, and finally Okuninushi of the Izumo kingdom “handed over the land” to an expeditionary force led by Takeikazuchi Okami, the deity of the Kashima shrine. The painting above is said to have been dedicated to Yahiko Shrine in Niigata, Koshino-kuni. Yahiko Shrine is in the same cultural sphere of the Sea of Japan, and the way of worship is the same as that of Izumo, two bowing, four clapping, two bowing, so it seems that the shrine was deeply related to Izumo and had a high “sense of kinship,” so to speak. It is possible that Izumo followed the “legitimate” procedure of handing over the land, though “unwillingly,” and that this information was conveyed to the Koshino-no-kuni and its people, and symbolized as “seeking approval” as in this picture.

This picture, on the other hand, depicts the “handing over of the country” omens, which was displayed in the precincts of Katori Jingu Shrine. It is said that the Katori no Kami accompanied the Kashima no Kami and joined the “handing over of the country” of the shell of Izumo. Please forgive the tree shadows on the picture screen, as they are the result of sunlight. He is posed with Kyotsunushi no Okami, the deity of the Katori Jingu Shrine, as the victor, to whom Izumo no Okuninushi offers a sword as a symbol of his military prowess. This can be seen as a unique expression of armed renunciation.

Japan is a country that started out in the world of mythology. As I mentioned the other day about ancient Rome, this is the backbone of a nation in terms of its legitimacy. The legitimacy of a nation may have various aspects and meanings, but at the very least, the fact that such a theory is persuasive is a strong basis for legitimacy.

At the starting point of the legitimacy of the Yamato kingdom, this deity of the eastern provinces appears as a symbol of the military force of national unity.

On either side of the Sakura Gate of the Kashima Jingu Shrine, there is a symbolic thunderbolt-like device, like the emblem of the great god Takemikazuchi, displayed as a “shizumu” (guardian deity), as shown in the photo. The shrine is also strongly tinged with a “warrior god” atmosphere.

Before the Meiji era, only Ise, Katori, and Kashima were given the title of “Jingu,” making it one of the most famous shrines in Japan. The Kanto region occupies a very special position in terms of its relationship to the myth of the handing over of the kingdom.

Despite the military role of the god of war and the symbolic presence of the warrior, the Kanto region was not the main stage of Japanese history for some time afterward.

Since the geographical location of the region is in a watery area such as the Katori Sea, Kasumigaura, and the Sea of Kashima, it is difficult to develop an agricultural economy of rice paddies. Was the deity’s lineage merely a symbolic authority? Was it difficult to create a concentrated power structure in a topographically disjointed country? In the end, was anarchic strife caused by the disorderly rise of independent agricultural owners the norm?

Later in Japanese history, a ruling structure by samurai was established in the Kanto region, and a state based on independent military power by farm developers, separate from the dynastic state, was established. I continue to be puzzled as to what relationship there may or may not be between this Kashima Shrine’s warrior deities and the Kanto region after this, which history has elucidated.

Posted on 8月 6th, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 日本社会・文化研究

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.