幕末明治の動乱期を経て、ようやく日本社会が新時代に向かって走り出そうとした時期。この奈良県十津川郷は勤皇の郷村として、明治維新戦争でも独自の存在感を示していた。司馬遼太郎の「街道をゆく」でも、この地の人びとのこの時期の気骨ある行動を丹念に記述している。

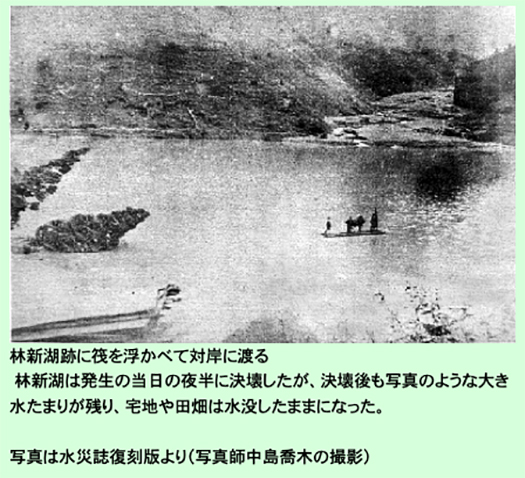

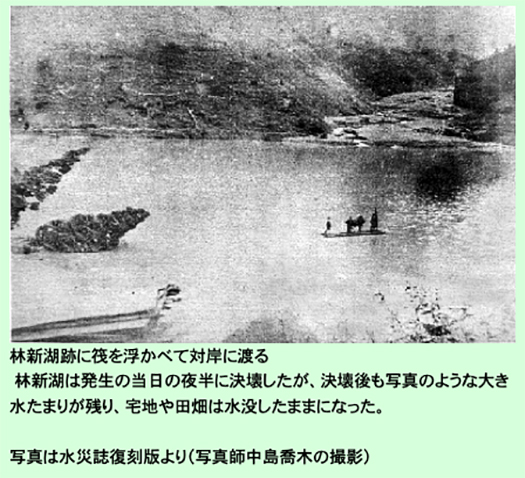

そのプライド高き郷村を明治22(1889)年大水害が襲う。1月16日にはオーストラリアで最高気温が記録(摂氏53度)されるような「異常気象」ぶりだったとされる。日本に於いても、春から気象条件が安定せず、梅雨時期には長雨、夏に入ると日照りが続いていた。それが8/17になって一転して豪雨が始まった。この雨風は丸2日経っても治まらず郷村を流れる「十津川」の水はあふれ、土砂崩れで民家は流れ出し、くずれた土砂が各所で川の流れをふさいで60ヵ所もの「湖水」が作られるほどだった。死者は168人、家屋流失・半壊610戸。耕地や山林にも大きな被害が出た。県をまたいで和歌山県では同じ河川が「熊野川」になるけれど、この被害は流域の熊野本宮大社・大斎原にも襲いかかり多くの社殿が流された。 流失を免れた上四社3棟は現社地に移設され、大斎原には流失した中四社・下四社をまつる石造の小祠が建てられている。それまでの大斎原の大社は、およそ1万1千坪の境内に五棟十二社の社殿、楼門、神楽殿や能舞台など、現在の数倍の規模だったという。

わたしは、この故事を胸に抱きながら年来の願望であった「熊野詣」を数年前に果たしたけれど、熊野から奈良県吉野に抜ける山岳地系、その谷地を縫うように流れる河川を体験しながら、北海道にも似た自然景観の荒々しさに深い感慨を受けていた。この地形と自然景観とが一体となって、日本社会に「熊野詣」という心象を形成したのだろうかと、北海道人としてなにか心理が通底するような思いを持った。

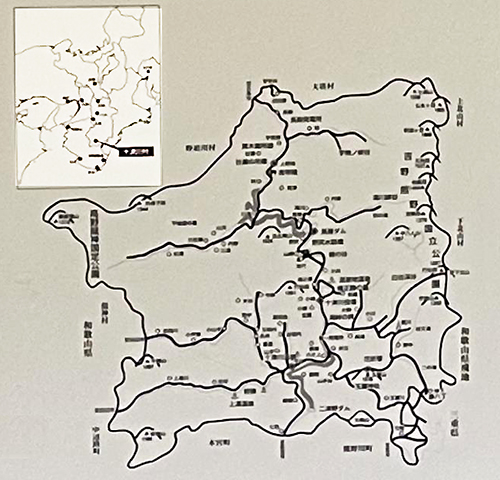

この未曾有の大被害からの復元を目指して、十津川郷村は立ち上がる。歴史的な維新期の行動力から、多くの人材が中央で活躍していて、そういったかれらが明治政府に対して国家的な復興策を建言し、政治的な成果を生み出していって、折からの北海道開拓・移住への支援策を勝ち取っていくことになる。

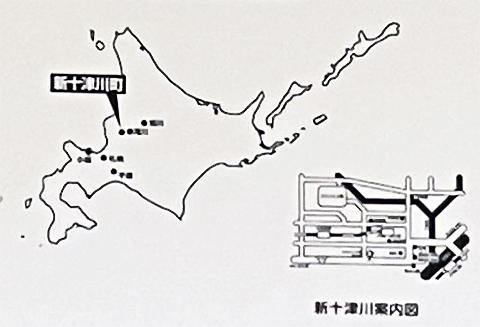

策定された北海道移住策に対して十津川郷村の移住希望者は総数600戸、2691名に上ったという。そして、同年10月には神戸港から北海道小樽に向けて出港した。北海道人としてなにか、血肉が騒ぐ思いが止まらない。

English version⬇

[Extreme weather and major flooding in 1889: Totsukawa River and the ‘New Totsukawa’ – 2].

The spirit of the entire township and village to rise up from the flood damage and move towards the development of Hokkaido in the Meiji era was violently shaken. …

This was a time when Japanese society was finally about to run towards a new era after the turbulent period at the end of the Edo and Meiji periods. This village of Totsukawa-go in Nara Prefecture was a hometown village of the Emperor and had a unique presence during the Meiji Restoration War. Ryotaro Shiba’s Kaido yuku (On the Road) also painstakingly describes the spirited actions of the people of this region during this period.

In 1889 (Meiji 22), the pride of the village was hit by a major flood, and on 16 January it was said to have been an ‘abnormal weather event’ with the highest temperature ever recorded in Australia (53 degrees Celsius). In Japan, weather conditions have been unstable since spring, with long rains during the rainy season and continued sunshine in summer. Then, on 17 August, the heavy rains started. The rain and wind did not subside even after two whole days, and the Totsu River flowing through the township overflowed, causing landslides that swept away houses and created as many as 60 ‘lakes’ in various places where the river was blocked by debris and sand. The death toll was 168, with 610 houses swept away or half destroyed. Arable land and mountain forests were also severely damaged. In Wakayama Prefecture, the same river is known as the Kumano River, but the damage also hit the Kumano Hongu Taisha shrine in the basin, Osaibara, and many of its buildings were washed away. The three buildings of the upper four shrines that escaped being swept away were moved to the present site of the shrine, and a small stone shrine dedicated to the middle four and lower four shrines that were swept away was built in Osaibara. The former shrine in Osaibara was several times the size of the present one, with five buildings, 12 shrines, a tower gate, a hall for Shinto music and dance, and a Noh stage, all within a precinct of approximately 11,000 tsubo (about 1.2 square metres).

I had this legend in mind when I fulfilled my long-held wish to visit Kumano a few years ago, and was deeply moved by the ruggedness of the natural landscape, which resembles that of Hokkaido, as I experienced the mountainous terrain that runs from Kumano to Yoshino in Nara Prefecture and the rivers that weave through the valleys. As a person from Hokkaido, I wondered if this topography and natural landscape had combined to form the mental image of ‘Kumano Pilgrimage’ in Japanese society, and as a person from Hokkaido, I felt as if my mind was somehow connected to this.

The village of Totsukawa-go is rising up to recover from this unprecedented damage. Due to the historical power of the Meiji Restoration, many people were active in the central government, and they proposed a national restoration policy to the Meiji Government, which produced political results and won support for the development and emigration of Hokkaido.

In response to the Hokkaido emigration policy formulated, a total of 600 households and 2,691 people wanted to emigrate to Totsukawa-go Village. In October of the same year, they set sail from the port of Kobe for Otaru in Hokkaido. As a person from Hokkaido, I can’t stop thinking that something is stirring in my blood.

Posted on 2月 19th, 2025 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 日本社会・文化研究 | No Comments »