わたしの年代は日本の戦後社会が起動していく1960年代が青春期。最初の東京五輪に向かって社会が大きく変貌していく時代だったけれど、それは同時に「モータリゼーション」が一般化して行く過程でもあった。わが家は食品製造業で札幌に居を構え、商品の「配送」にクルマが導入されて、事業の拡大に連動してその数が飛躍的に増えていった。

都市基盤として道路整備が進んで舗装道路が拡張していった。当初は寒冷地用の道路整備の手法に不備があって、冬の間に凍上で凸凹道路被害が頻出した。やがて凍結深度以下までの道路整備が進んで「移動の自由」社会が、本格的に日本列島に根付いていった。

そういう社会変化の最中に生きてきた人間としては、移動の自由の確保手段はクルマということになるのだけれど、しかし人間社会としては、それ以前、そういう機能を果たしていたものとして一家に一台というように機能していたのは、水上交通を利用した「丸木舟」だろう。

海の「京町家」といわれる伊根の舟屋の「街並み」海から見る家々のありよう、その海岸線に張り付いた各戸ごとに舟を収容している光景は、まさに現代住宅の「カーポート」さながらだった。

主に海民文化としての漁撈などに使われたとされるけれど、まことに人類的な「移動の自由」が確保されたものだと目に焼き付いていた。

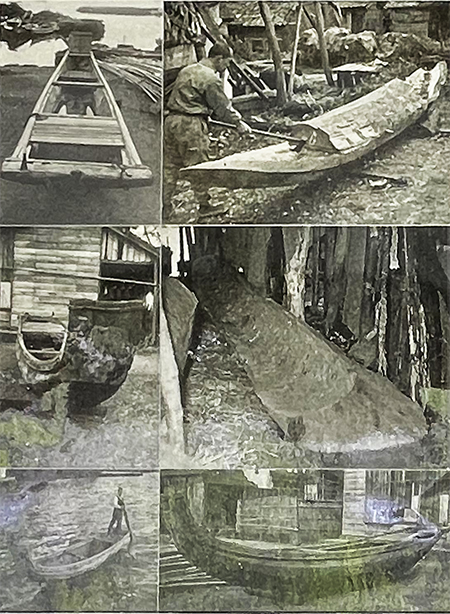

今回、大阪豊中の古民家園でこうした丸木舟の展示があったので、ついピンナップした。

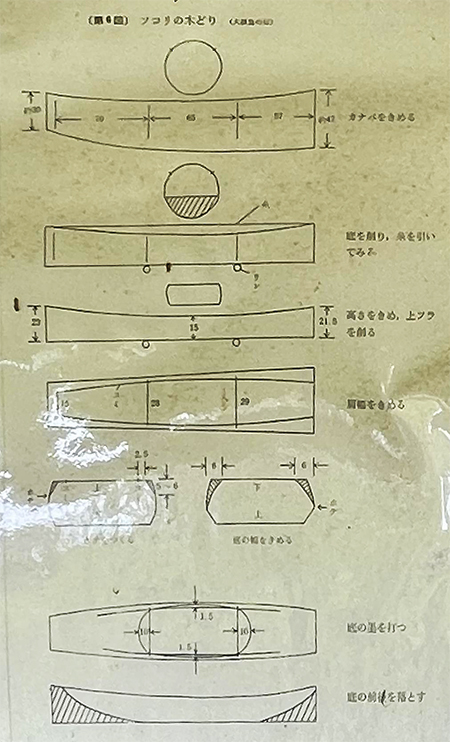

ここでは丸木舟という呼称ではなく「刳舟〜くりぶね」という呼称が冠されていた。「刳」という文字はいかにも「くり抜く」という行為を彷彿とさせる語感を持っているけれど、制作プロセスの開示説明からは非常に直接的な表現と実感させられる。

上の写真の奥の舟は島根県の「反り小舟〜ソリコブネ」。1970年代くらいまでは島根県の「中海」で利用され赤貝取りには特有の「ローリング」がとても都合が良かったという解説。クルマの「小回りが利く」みたいな「運転感覚表現」と似通っていて、興味深く体感的にも納得できる。

写真の手前側は奄美大島地方で使われていた「クリ舟(スブネ)」。マツ・イジュ・タブなどの丸木をそのままくり抜いた長さ3mほどの小舟で江戸時代後期には200艘地殻が活動していた記録があるという。村人の共同作業で制作されたこの舟で、2−3人乗りでサワラ突き・キビナゴ漁・イカ引きなどの島特有の漁を行ってきた。現代で舗装道路に乗りだして郊外スーパーに買い出しに行く、みたいな生活感覚とも通底するように思ってしまう。

原初的な人間の「移動の自由」をまざまざと感覚させられる。

English version⬇

Before the advent of the car, the “wooden boat” was a tool for human free movement.

A traditional means of free movement that is metaphorically similar to the modern “personal car. I really sympathize with the unique rolling motion of the boat in the familiar sea, which was used for fishing. I have a lot of sympathy for the “rolling” of the boat in the sea around us.

I was an adolescent in the 1960s, when Japan’s postwar society was starting up. It was a time of great social transformation toward the first Tokyo Olympics, but it was also a time when “motorization” was in the process of becoming commonplace. My family was in the food manufacturing business and located in Sapporo. Cars were introduced to “deliver” products, and the number of cars increased dramatically as the business expanded.

As the city infrastructure was developed, paved roads were expanded. In the beginning, the road maintenance methods for cold regions were inadequate, and uneven road damage occurred frequently due to freezing during the winter. Eventually, roads were built to below freezing depths, and a society of “freedom of movement” took root in the Japanese archipelago in earnest.

For those of us who have lived in the midst of such social changes, the car is the means of ensuring freedom of movement, but what functioned in human society before that time, as if there was one car in the family, was the “marukibune,” a boat that used water transportation.

The “townscape” of the boathouses in Ine, which are called “kyo-machiya” of the sea, and the sight of the houses seen from the sea, with each house having a boat attached to the shoreline, is just like a “carport” of a modern house.

The houses are said to have been used mainly for fishing as part of the seafaring culture, but I was impressed by the freedom of movement that was secured in the houses.

This time, I saw an exhibition of such wooden boats at an old private house garden in Toyonaka, Osaka, and I couldn’t resist pinning them up.

The boats were not called “marukibune,” but rather “kuribune,” which means “dugout boat. The word “kuribune” is reminiscent of the act of “hollowing out,” but the description of the production process makes me realize that it is a very direct expression.

The boat in the back of the photo above is Shimane Prefecture’s “Sorikobune,” which was used in the “Nakaumi” region of Shimane Prefecture until around the 1970s, and its unique “rolling” characteristics made it very convenient for catching red clams. It is similar to the “driving sensation expression” of a car, such as “small turn”, which is interesting and satisfying from a physical point of view.

In the foreground of the photo is a “kuri-bune” used in the Amami Oshima region. It is a small boat about 3m long made of hollowed out round pine, iju, tabu and other trees, and there is a record of 200 boats with crusts being active in the late Edo period. These boats were made by the villagers’ joint efforts, and 2-3 people used them for fishing such as Spanish mackerel poking, kibinago fishing, and squid pulling, which are unique to the island. It seems to have a similarity to the modern way of life in which people take to the paved road to go shopping at a suburban supermarket.

It gives us a vivid sense of the primitive “freedom of movement” of human beings.

Posted on 4月 21st, 2024 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 歴史探訪

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.