仕事上の立場に大きな変化があって、ある程度の自由な環境を意識するようになってくると、自分の本然としての数寄の部分にこだわりが強まってきますね。わたしの場合には全国の古民家とか、古建築とか、もっと言えば昔人との対話のようなものが中心領域。どんな家で暮らしていたか、どういう思いを抱いて日々の暮らしを過ごしていたか、という部分に興味が集中する。わたしの場合、日本人の歴史。

古墳は仏教導入によってその大きな役割が「寺院」に転換させられていったというのが定説になってきている。ある時期まで全国でさかんに造営されたものが一斉に文化継承されなくなったことが、そのことをあきらかにしているのでしょう。

イラスト群は千葉県芝山の「芝山古墳・はにわ博物館」展示から。古墳の造営がなぜ、どのように行われていったのかについて非常にわかりやすく解説されていた。

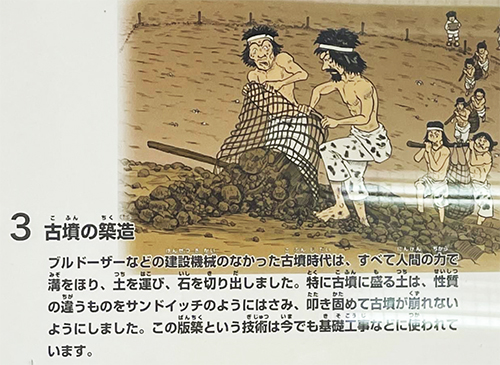

日本列島では長い縄文的ライフスタイルの伝統的社会があって、そこに稲作というあらたな生産手段革命が導入された。そのとき農業土木というまったく新規な産業革命要素が同時並行した。それまでの狩猟採集という食糧獲得手段に対して、植物管理型の食糧資源でありその生産装置として、数学的土木改造技術、水を管理する必要からの土木工事に、労働力の集中投入が不可欠だったことでしょう。

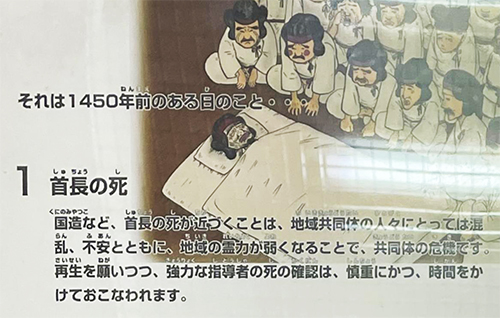

そういった土木事業には当然、その全体を構想し企画立案して人工(にんく)を指揮命令して動員する体制というものが必要だった。そういうことで東アジア全域からニューフロンティアとして移住してきた集団は、ここ関東地域にも土地を得て入植していった。そういった集団の首長には、全体を統御する「権力」が自然に備えられていった。

古墳というものには、そういう集団的土木事業と「権力」構造の生成が表現されている。

その後、中国大陸で強大な中央集権的国家が出現することで、それへの国際的対応としてこれら各地域権力を統合する必要が生まれていった。ヤマト王権は、こうした国内の有力層をまとめあげていく必要性から、威信材文化を付与させる必要性に迫られ、さまざまな下賜品を下していった。

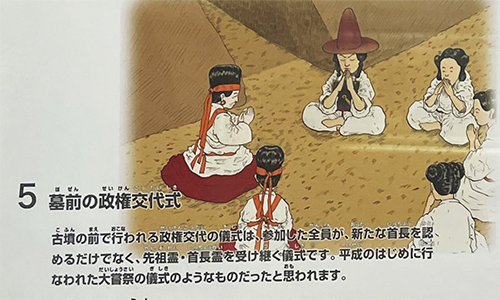

けれど、最終的には地域権力自身の「正統性」を民人に認定させる目に見える行為規範が求められて、前方後円墳のような「権力交代儀礼装置」を各地の地域権力に波及させていった。

そんなふうに思える。古墳の造営の労働力とは、結局、田んぼを作って行く土木労働を基盤とした権力交代儀礼であり、その形象化のように思える。

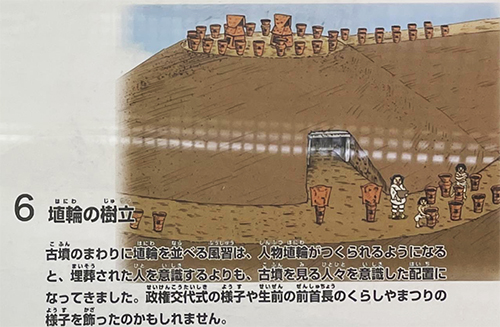

埴輪は古墳の周りに並べられていったけれど、その向きは外から古墳を見る人の視線に向けられていたというのは、そういった事情を色濃く映し出しているのでしょうか。

English version⬇

Chiba Shibayama Kofun Tumulus Exploration -1

Kofun tumuli were constructed actively until a certain period, and then they were replaced by Buddhist temples at once. I would like to take a macroscopic look at the background circumstances. The following is the background of the construction of the tombs.

As my work position undergoes major changes and I become more conscious of a certain degree of freedom in my environment, I am becoming more and more focused on the sukiya part of my nature. In my case, my main areas of interest are old private homes and old architecture from all over Japan, or more specifically, dialogue with people from the past. My interest is focused on what kind of houses they lived in and what kind of thoughts they had as they lived their daily lives. In my case, the history of the Japanese people.

It is becoming a common theory that the introduction of Buddhism converted kofun tombs into “temples” that played a major role in the history of Japan. The fact that the cultural inheritance of what had been actively built throughout the country until a certain period of time has ceased all together is probably revealing this fact.

The illustrations are from an exhibition at the Shibayama Kofun Tumulus and Haniwa Museum in Shibayama, Chiba Prefecture. The exhibition provided a very clear explanation of why and how the construction of kofun tumuli took place.

The Japanese archipelago had a long tradition of Jomon lifestyle, to which a new revolutionary means of production, rice cultivation, was introduced. At the same time, a completely new industrial revolutionary element, agricultural engineering, was introduced at the same time. In contrast to the hunter-gatherer means of acquiring food, which had been used until then as a plant-managed food resource and production device, it was essential to invest a concentrated amount of labor in mathematical civil engineering modification techniques and in civil engineering work that was necessary to manage water.

Such civil engineering projects naturally required a system to envision and plan the entire project, and to command and mobilize manpower. Therefore, groups of people from all over East Asia migrated to the Kanto region as the new frontier, and they acquired land and settled here as well. The leaders of these groups were naturally equipped with the “power” to control the entire region.

Kofun tumuli express such collective civil engineering projects and the creation of a “power” structure.

Later, with the emergence of a powerful centralized state on the Chinese mainland, it became necessary to integrate these regional powers as an international response. The Yamato kingdom was compelled by the need to unite these powerful domestic powers and to grant them prestige and culture, and it bestowed a variety of gifts upon them.

Ultimately, however, the need for a visible code of conduct that would allow the people to recognize the “legitimacy” of the regional power itself led to the spread of “ceremonial devices for changing power,” such as the anterior-rectangular mounds, to regional powers in various regions.

That is how it seems to me. The labor power of building the tombs was, after all, a ritual of power-shifting based on civil engineering labor to build rice paddies, and it seems to be a figuration of such a ritual.

The fact that the haniwa were arranged around the burial mound but oriented to the gaze of those looking at the burial mound from the outside is a strong reflection of this situation.

Posted on 11月 30th, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 日本社会・文化研究, 歴史探訪

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.