さて東京上野の「下町風俗資料館」展示から、こども文化の推移について掘り起こしてきた。個人的に肉体体験のある「紙芝居」や「パッチ(メンコ)」のことを辿ってみると、子ども文化としての「いつの世も変わらない」部分が浮き彫りになってくる気がしてならない。

とくにメンコについてはその出自が江戸時代まで確実に遡れる証拠があると見せられると、人間本然の部分での「感受性」で江戸期のこどもたちとも深い共感を強く持つようになる。ただ、その本然が時代によってさまざまな表情を見せるだけなのだというように気付かされるのだ。

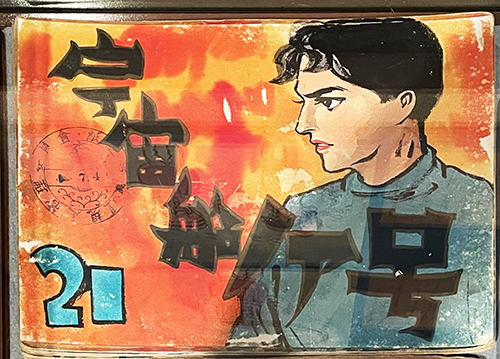

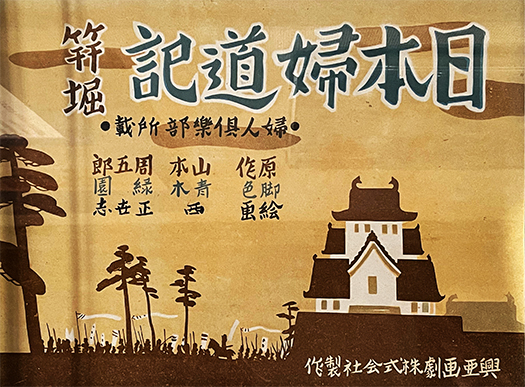

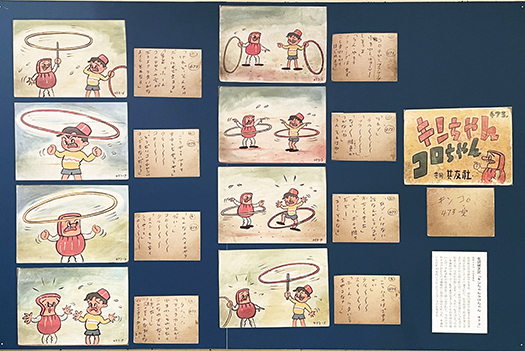

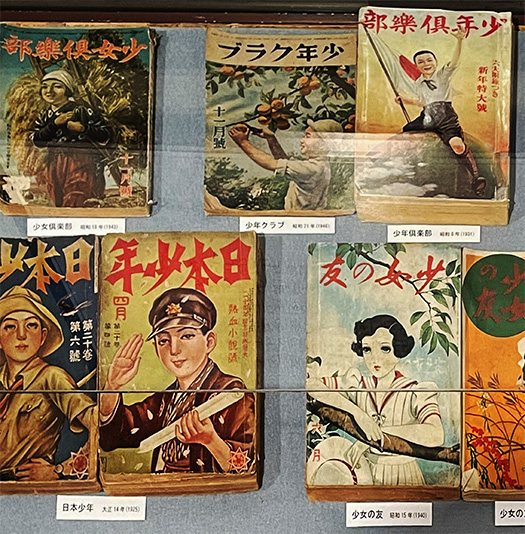

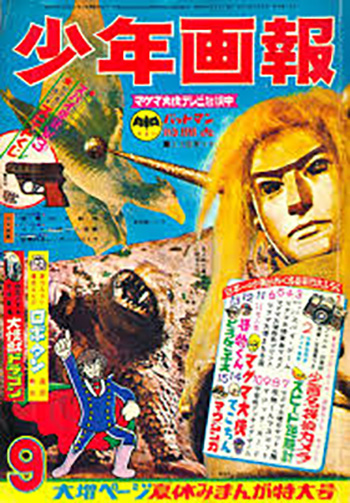

そうした幼少期体験の基底的「文化性」は、わたしたち戦後世代としては子ども向け雑誌=マンガ雑誌へとメディア化していった。展示資料では写真のような少年・少女雑誌が提示されていた。これらの雑誌にはわたしは記憶がなく、わたし年代より以前の子どもたちに愛読されたものなのだろうと思う。

その選択が兄弟たちの共通的選択だったのかどうか不明だけれど、わたしは「少年画報」という雑誌にどっぷりとハマり込んでしまっていた(笑)。

基本的には紙芝居由来の「ストーリーマンガ」に圧倒的にのめり込んでいた。不思議なものでこういう特定メディアに惹き付けられると「その世界から世間を見る」みたいな感覚に襲われていたと思う。

この雑誌では他誌で華々しく一世を風靡していた手塚治虫作品がなかなか掲載されなかったのが、あるとき「マグマ大使」という作品が登場した。そのときすでに「眼光紙背に徹して」いた少年期のわたしは、出版社と大作家・手塚治虫さんとのビジネス的な交渉とか関係性までをおもんばかるようにまでなっていた。「あれ、どうも関係がうまくいってないんじゃないか・・・」みたいな(笑)。特定メディアから知らず知らずに影響される党派制・立場のようなものに縛られていたように思うのだ。

その後、自分自身が出版=メディアというビジネスの周辺領域で生きるようになった内面的な動機を占めているのかもしれない。

English version⬇

Cultural Consolidation into “Magazine Media” for Children: Postwar Children’s Culture-5

Children’s culture became a medium of manga magazines in postwar society. The dramatization and supplement culture sublimated the picture-story show and menko culture. The…

Now, I have been digging into the transition of children’s culture from the “Shitamachi Fuzoku Shiryokan” exhibition in Ueno, Tokyo. When I trace back to my personal physical experience of “picture story shows” and “patches (menko),” I cannot help but feel that the “unchanging” aspects of children’s culture come to the fore.

In particular, when we are shown evidence that the origin of menko can be traced back to the Edo period (1603-1868), we can strongly sympathize with the children of the Edo period in terms of their “sensitivity” to human nature. However, they realize that this naturalness only shows different expressions depending on the time period.

The fundamental “cultural nature” of such childhood experiences became media for us, the postwar generation, in the form of children’s magazines (manga magazines). In the exhibition materials, magazines for boys and girls like the one shown in the photo were displayed. I have no memory of these magazines, and I think they must have been read by children before my generation.

I am not sure if this was a common choice among my brothers and sisters, but I was completely absorbed in a magazine called “Shonen Gaho” (laugh).

Basically, I was overwhelmingly absorbed in “story manga” derived from picture story shows. It is a strange thing, but when I was attracted to this particular media, I felt as if I was “looking at the world from that world.

One day, however, “Magma Ambassador” appeared in the magazine. At that time, I was already “devoted to the light of the eye,” and I had come to care about the business negotiations and relationship between the publisher and the great author, Tezuka Osamu. I was even concerned about the business negotiations and relationship between the publishing company and the great author Osamu Tezuka. (laugh). I think I was bound by a kind of partisan system or position that was unknowingly influenced by certain media.

Perhaps this accounts for the internal motivation that led me to live on the periphery of the business of publishing=media.

Posted on 2月 24th, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 日本社会・文化研究 | No Comments »