鹿島神宮のことについてちょっと巨視的という感じで6回のブログシリーズで書いてみました。

写真は鹿島神宮の楼門、拝殿正面、本殿の主要な建築装置3例。こういった建築デザインには、わたしたち日本人の美的感受性が集中していると感じます。目に鮮やかな丹色の結界装置。ひろく人びとを受け入れる神域との出会い装置、そしてややキッチュな装飾性をまとったカラフルな本殿神域。それぞれの建築デザインが、わたしたちの感受性にこころよく響いてくる。

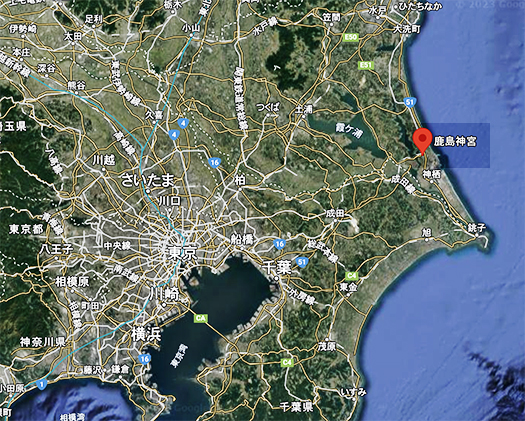

自分なりの感想として、日本文化としての鹿島神宮という存在は畿内地域での伊勢神宮とパラレルな位置にあるのではないかという実感。

伊勢神宮は畿内地域に対して「夏至の日が昇っていく」方角に位置していて、古来からの太陽神信仰に深く根ざしているという印象。そして内宮と外宮がワンセットのようになっている。

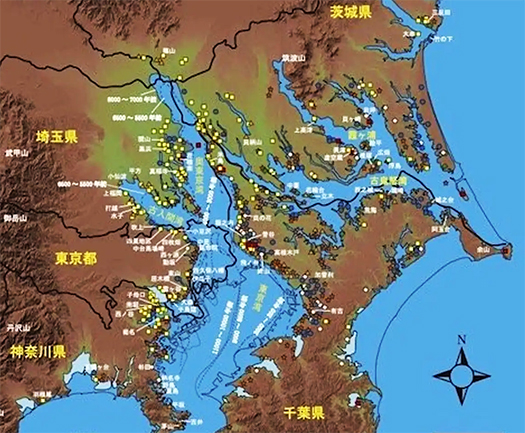

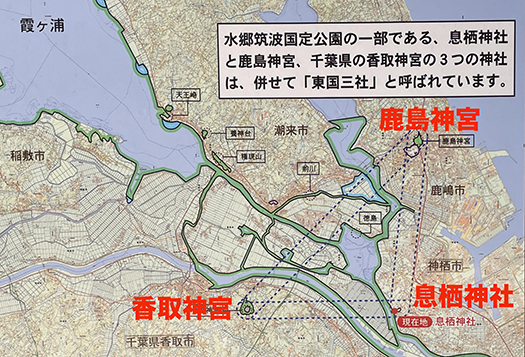

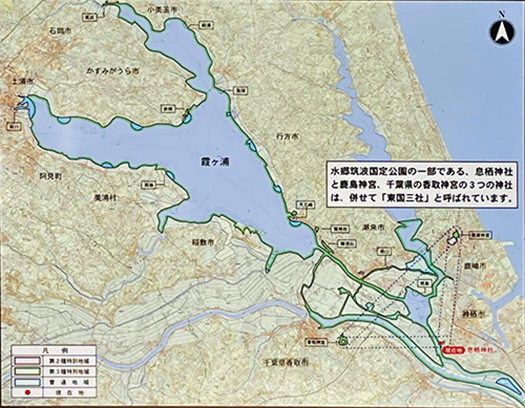

この鹿島神宮と香取神宮はこの伊勢の内宮・外宮の関係と似つかわしいように思う。地理的な位置としては関東圏にとって「夏至の日が昇っていく」方角という配置位置に相当するように思える。神道という列島社会古来の宗教文化の基盤にはこうした自然崇拝があるのでしょう。

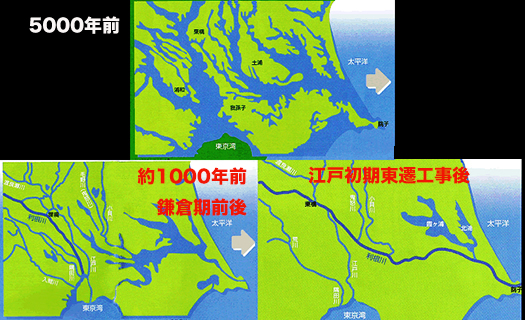

で、こうした日本列島的「自然崇拝」思想には、四季変化が明瞭であり、さらに目に見える地面の状況それ自身も千変万化するという世界の中でも特異な「うつろう」自然という基盤があると思う。

大陸民族の場合は、不変なるものへの帰依が基本の心性としてあるように思う。悠久であるもの、かわらないものが基本ではないか。キリスト教的な一神教世界観とも通じる考え方。それに対して日本的な自然環境の中では、万物は生々流転するという思想が優勢になる。

そんな基盤から「もののあはれ」というような「ためいき」のような思想が基底的なものになるように思えてならない。たしかに自然の大地そのものが生々流転する様子を民族記憶として刷り込まれていけば、万古不変という考え方が後退し、そのように柔軟に受け入れる思想が大勢になると思える。加えて言えば日本列島は太古以来、地震や火山噴火、台風などの自然災害とも共生してきた。

東国三社といわれるなかでも中核と思える鹿島神宮篇を書き終えてみると、このような日本人の精神性を育んできたものとの遭遇を強く意識させられた次第です。

こちらは樹齢800年と言われる大鳥居横の「椎の木」。ブナ科の常緑高木。昔は家の周囲に「防火樹」として使用されたのだとか。木に「防火」させるというのは面白い考え方だなぁ、と。でも本当はシイタケの原木だということなので、日本人の味覚の奥深くのキノコ文化を継承してきた存在として、家の近くに栽培してきたのかも知れませんね。

関東古来からの日本人的文化性の象徴、そんな印象を強くした鹿島神宮でありました。

English version⬇

Kashima Jingu Shrine, the Cradle of Changing Views of Nature: An Exploration of the Three Shrines of Higashikuni – 6

Earthquakes, typhoons, volcanoes, and even the land itself are visibly transforming the view of nature in the Japanese archipelago. Kashima is a sacred place where “gods dwell” in the midst of these changes. Kashima, a Shinto shrine where “the gods dwell” amidst such circumstances.

I have written about Kashima Jingu Shrine in a six-part blog series that is a bit macroscopic.

The photos show three examples of the main architectural devices of Kashima Jingu: the Sakura-mon Gate, the front of the worship hall, and the main shrine. I feel that the aesthetic sensitivity of the Japanese people is concentrated in these architectural designs. The Tan-colored warding device is vivid to the eye. The main hall is a colorful, kitschy, and decorative space. Each of these architectural designs resonates with our sensitivity.

My own impression is that the existence of Kashima Jingu Shrine in Japanese culture is in a parallel position to that of Ise Jingu Shrine in the Kinai region.

Ise Jingu is located in the direction of the “rising sun on the summer solstice” in the Kinai region, and I have the impression that it is deeply rooted in the ancient belief in the sun god. And the inner and outer shrines are like one set.

The Kashima Jingu and Katori Jingu seem to be similar to the relationship between the Inner and Outer Shrines of Ise. In terms of geographical location, they seem to be located in the direction of the “rising sun on the summer solstice” in the Kanto region. This kind of nature worship must be the basis of Shinto, the ancient religious culture of the archipelago.

This nature worship in the Japanese archipelago is based on the unique nature of the world, with its distinct seasonal changes and the visible ground itself undergoing a multitude of changes.

In the case of continental peoples, I think their basic mentality is to take refuge in what is unchanging. The eternal and unchanging is the basis. This is a way of thinking that is also compatible with the Christian monotheistic view of the world. In contrast, in the Japanese natural environment, the idea that all things are born and flowing is predominant.

From such a foundation, the idea of “mono no ahare,” or “tameiki,” seems to be the basis of the philosophy. Indeed, if the natural land itself is imprinted with the memory of the birth and transmigration of nature as a national memory, the idea of “eternity” will recede and the idea of flexibility and acceptance will become the prevailing thought. In addition, since time immemorial, the Japanese archipelago has coexisted with natural disasters such as earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and typhoons.

When I finished writing the Kashima Shrine, which I consider to be the core of the three shrines in the eastern part of Japan, I was made keenly aware of the encounter with the things that have nurtured the spirituality of the Japanese people.

This is a “Shiinoki” (vertebrate tree) next to the Otorii gate, said to be 800 years old. It is a tall evergreen tree of the beech family. In the old days, it was used as a “fireproof tree” around houses. I thought it was an interesting idea to make a tree “fireproof. But the truth is that it is the original source of shiitake mushrooms, so perhaps it has been cultivated near the house as an inheritor of the mushroom culture deep in the Japanese palate.

The Kashima Jingu Shrine gave me such a strong impression, a symbol of Japanese cultural characteristics from the ancient Kanto region.

Posted on 8月 10th, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 日本社会・文化研究 | No Comments »