日本の歴史を見ていると、宗教と政治状況というものは密接に絡み合いながら歴史プロセスが紡がれてきていたことがありありと伝わってくる。この関東シリーズでも龍角寺を探訪したけれど、地域権力の正統性を担保する「宗教的」施設として古墳の造営が盛んに行われたものが、仏教という新たに導入された世界宗教が王権によって積極的に普及促進された結果、古墳から仏教寺院造営に権力のシルシ、目に見える権威表現が変換していったその端境期の様子が見えてくると思う。

八百万の各地域毎の正統性訴求としての神社なども、このような流れのひとつだったのだろう。

中央王権はその正統性訴求の大きな目標として「征夷」という中国式の国家観を導入した。アジア世界の中で中国に成立した「華夷・中華思想」にならって、攻撃すべき外敵として異民族を挙げて国家の集権性を高めようとしたものだろう。それが当時の最先端の近代国家思想だった。

日本の王権はその征夷ターゲットとして東北地域を据えた。『日本書紀』景行天皇二七年二月条(2世紀代と仮定される)に東国視察後ヤマトに帰還した武内宿祢(たけうちのすくね)が「東夷の中に日高見国有り。其の国の人、男女並に椎結文身(入れ墨の風習)し為人勇悍なり。是総べて蝦夷と曰ふ。亦土地(くに)沃壌にして曠(ひろ)し。撃ちて取るべし」との記述。

いきなり「撃ちて取るべし」と過激な侵略宣言を行っている。

こういう中央王権が東国支配を進めていく過程で、それまで独自発展していた地域権力の中で勢力の変化が起こっていった。関東ではより武権的な勢力が地域を把握していったと思える。地域権力と中央王権との間でのさまざまな思惑と人事などが交叉していった経緯をうかがわせる。ヤマトタケルの説話などはそうした経緯を寓話的に表現したものだったのだろう。

鹿島神宮にしろ香取神宮にしろ、武神として性格が描かれるのは、こういう背景事情だったのではと思われる。日本全体の中で香取の海を挟んで鹿島と香取は、「東海道」の交通の最重要地点として認識されていった。神格としてこの2社が伊勢とも同格扱いだった理由と思える。

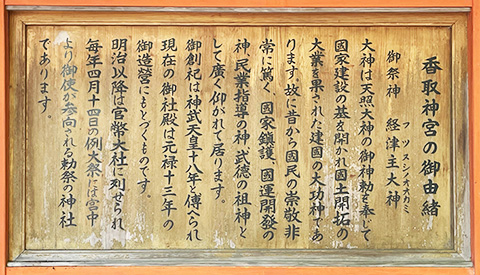

そのように香取神宮の社域を見ると門が2箇所にあり、一種の「城郭」風。写真は「総門」で社域の結界をあらわし、その隣には「勅使門」(3番目の写真)がある。この塀の中には香取神宮の最上位の神官が住居して、王権の使者を迎賓していたのだという。

古代では神官という存在はそのままに神官だとは思えない。人びとに対して「神である」と宣命することがいちばんてっとり早く服従させる、正統性根拠になったに違いない。

北海道で出版という事業を始めてその後東北に進出して、この王権による「征夷」について多くの学びがあった。いま、関東地域に再度接してみると、いろいろな見方に気付かされる思いがしている。

English version⬇

So-mon Gate and Imperial Envoy Gate, Katori Jingu Shrine (2) Exploration of Three Shrines in Eastern Japan-16

The Imperial Gate, which represents the high status of Katori Jingu Shrine. Katori Jingu is located on both banks of the Katori Sea, an important transportation hub on the Tokaido Highway, in Kashima and Katori. Domestic governance was also important and was controlled by the “military authority”?

Looking at the history of Japan, we can clearly see that religion and political situations were closely intertwined in the historical process. As we visited Ryukaku-ji Temple in this Kanto series, the construction of kofun (burial mounds) was actively practiced as a “religious” facility to ensure the legitimacy of local power, but as Buddhism, a newly introduced world religion, was actively promoted by the royal power, the sills of power and visible expressions of authority shifted from kofun to the construction of Buddhist temples. As a result, the sills of power and visible expressions of authority were transformed from ancient burial mounds to the construction of Buddhist temples.

Shrines and other forms of worship that appealed to the legitimacy of each of the 8 million regions were probably a part of this trend.

The central kingship introduced the Chinese concept of “conquering the barbarians” as a major goal of its legitimacy appeal. Following the “Huayi/Chinese ideology” established in China in the Asian world, the central kingship probably tried to enhance the centralized power of the state by identifying foreign peoples as external enemies to be attacked. This was the most advanced modern state ideology of the time.

The Japanese royal power set the northeastern region as the target of its barbarian conquests. In the second month of the 27th year of Emperor Keiko’s reign (assumed to be in the 2nd century), Takeuchi no Sukune, who returned to Yamato after visiting the eastern provinces, wrote in the Nihon Shoki (Chronicles of Japan), “Among the eastern barbarians, there is Hitakami province. The people of this land, both men and women, are fearless because of their tattooed bodies. They are all called Emishi. The land is fertile and spacious. We must shoot them and take them.

This is a radical declaration of aggression.

In the process of the centralized royal power’s domination of the eastern provinces, a change of power took place in the regional powers that had developed independently until then. In the Kanto region, it seems that a more militaristic power gained control over the region. This suggests the history of the interplay of various agendas and personnel matters between the regional powers and the central royal authority. The legend of Yamatotakeru may have been an allegorical expression of this process.

The reason why Katori Jingu, whether Kashima Jingu or Katori Jingu, is portrayed as a warrior god may be due to these background circumstances. In the whole of Japan, Kashima and Katori, across the sea from Katori, became recognized as the most important point of traffic on the “Tokaido” highway. This seems to be the reason why these two shrines were treated as equal to Ise in terms of divine status.

Looking at the shrine area of Katori Jingu, there are two gates, which give it a kind of “castle-like” appearance. The photo shows the “So-mon Gate” (the main gate), which marks the boundary of the shrine area, and the “Teshimon Gate” (the third photo) is next to it. Inside this wall, the highest-ranking priest of the Katori Jingu resided and welcomed the emissaries of the royal authority.

In ancient times, priests were not considered to be priests as they were. The most immediate and legitimate means of commanding people to obey him was to proclaim that he was a god.

I have learned a lot about the “conquest of the barbarians” by this royal authority when I started my publishing business in Hokkaido and later expanded to the Tohoku region. Now that I have come into contact with the Kanto region again, I am reminded of many different ways of looking at it.

Posted on 8月 21st, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 日本社会・文化研究, 歴史探訪

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.