さて国立歴史民俗博物館の「稲作」のパネル展示中で

ふと気付き、深くとらわれてしまったイラストが一番上の表現。

稲作というのは実にたくさんの労働を1年間かけて営んでいく営為。

コメという字は八十八であり百姓とはたくさんの労務を表す。

自然の季節変化を「読み取って」苗を植え季節の変化に即して

たくさんの労働を集中させた末にようやく秋の収穫を迎える。

抜けがたく自然の移ろいとともにある経済活動ということになる。

そうすると自然の気候に対して雨乞いをしたりすることが必須になる。

縄文の世でもそういう自然への祈りというものはあったにせよ、

弥生の食糧獲得手段の稲作にとって、自然気候への祈りはより必須化した。

縄文の最大の「生産手段」が人間力であり、そこでの祈りとは

人間の「生と死」への祈りが祭祀の主要なテーマだっと思えるのに対し

弥生ではより自然コントロールの志向性が大きくなったと思われる。

狩猟採集段階の食糧獲得の祈りと、農耕段階の祈りとでは様相が一変し、

農耕の年間作業に並行していったことが容易に想像できる。

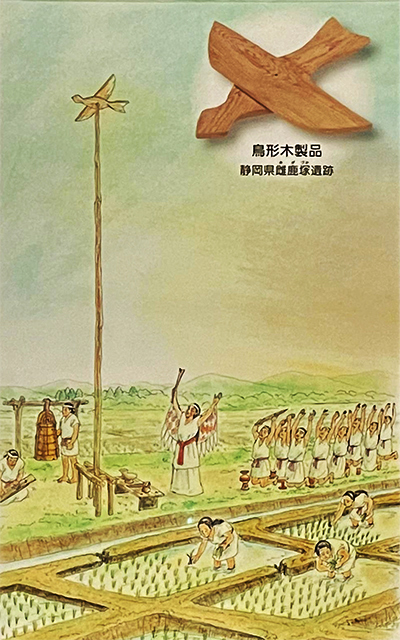

稲作文化では、鳥は「稲霊」を乗せて運ぶものと考えられていたという。

イラストは「東海地方の2世紀頃の事例を参考に、鳥形木製品を用いて

穀物の霊である稲霊〜いなだま〜を呼び寄せ、田の神に豊作を祈る

田植え時の「まつり」の様子を想像・復元したもの」という。

直感的には卑弥呼という存在や「八咫烏」を想起させるに十分。

農耕社会の祈りは「まつり」需要として独自のシャーマンを生み出し、

それが年間の季節変化に随順してスケジュール化した。

そういうシャーマン個人が持っている運の力で弥生のムラ社会に

結果恩恵をもたらせば、人びとの尊崇を集めたことは容易に想像できる。

「鬼道をよくする」卑弥呼が現世利益と直結していたのだと思う。

まつりは、スケジュール化されていくことで「まつりごと」化する。

稲作農耕は集団作業であり、指揮命令系統は組織化されていく。

洋の東西を問わず、農耕社会と政治・宗教は一体となって進化していく。

やがてヤマト王権・神武が奈良盆地に「東征」してきたとき

八咫烏が先導していたという神話は、このイラストのような信仰が

ひとびとのこころの基底に伏線として存在したことを暗示するのではないか。

またさらに下のイラストでは収穫のコメを高床倉庫に運ぶと理解できるけれど

その高床倉庫には神社建築に特徴的な「千木」がこっそり描かれている(笑)。

どうも国立歴史民俗博物館のみなさんの「刷り込み」は面白い。

このあたりの狩猟採集社会から農耕社会へのこころの変容について

見える化させたいものだと強く思う。

またこうした「まつり」の実相は稲作農耕のアジアでの出現地である

揚子江河口域ではどうだったのか、文化の比較にも興味を持つ。

English version⬇

Rice Culture, Prayer, and Agricultural Rituals: A 37,000-Year History of the Japanese Islands – 26

Rice cultivation and agriculture necessitated “matsuri” rituals and “goddesses” as priestesses. The wooden bird shape carrying the rice spirit is reminiscent of the yatagarasu (three-legged crow) of the Shinmu expedition. ・・・・・・.

Now, during the “Rice Cultivation” panel exhibition at the National Museum of Japanese History

I suddenly noticed an illustration at the top of the page that caught my attention.

Rice cultivation is an activity that involves a great deal of labor over the course of a year.

The character for “rice” is 88, and the word “peasant” represents a lot of labor.

The farmer “reads” the seasonal changes in nature, plants seedlings, and concentrates his labor in accordance with the changes in the seasons.

After concentrating a great deal of labor in accordance with the seasonal changes, the harvest finally arrives in the fall.

It is an economic activity that is inextricably linked to the changes of nature.

In this way, it is essential to pray for rain in response to the natural climate.

Even in the Jomon period, there were prayers to nature.

However, in the Yayoi period, when rice cultivation was the means of obtaining food, praying to the natural climate became even more essential.

The Jomon’s greatest “means of production” was human power, and prayer in this context meant

Prayer for human “life and death” seems to have been the main theme of rituals, whereas in the Yayoi period

In the Yayoi period, however, the emphasis seems to have been more oriented toward control of nature.

Prayers for the acquisition of food during the hunter-gatherer stage and prayers during the agricultural stage seem to have changed drastically, with the latter being more in line with the annual work of agriculture.

It is easy to imagine a parallel to the annual work of agriculture.

In rice culture, birds were thought to be carriers of “rice spirits.

The illustration is “based on examples from the Tokai region around the 2nd century, using bird-shaped wooden objects.

The “festival” at the time of rice planting to call the “rice spirit” (Inadama), the spirit of grain, and pray to the god of rice fields for a good harvest.

The illustration is said to be an imaginative reconstruction of a “festival” held at the time of rice planting.

Intuitively, it is enough to remind us of the existence of Himiko or “Yatagarasu,” the three-legged crow.

Prayer in an agrarian society created its own shaman as a “matsuri” demand.

This became a schedule that followed the seasonal changes of the year.

If the power of luck possessed by these individual shamans could bring benefits to the Yayoi village society, it would be possible for the shamans to become a part of the community.

It is easy to imagine that such individual shamans would have been revered by the people of the Yayoi period if they brought benefits to the village society.

I believe that Himiko, who “makes the path of demons better,” was directly connected to the benefits of the present world.

Matsuri becomes a “festival event” as it becomes scheduled.

Rice cultivation is a collective work, and the chain of command becomes organized.

Regardless of whether in the East or the West, agricultural societies, politics, and religion evolved in unison.

Eventually, when the Yamato royal authority, Jinmu, came to the Nara Basin on his “eastern expedition,” he was led by Yatagarasu.

The myth of Yatagarasu leading the way is an illustration of the belief that

The myth that Yatagarasu led the way during the Yamato Kingdom’s “eastward conquest” of the Nara Basin may suggest that beliefs like those in this illustration existed as foreshadowing in the hearts of the people.

In the illustration below, the rice harvest is carried to a warehouse on stilts.

In the illustration below, we can understand that the rice harvest is carried to a warehouse on stilts, but the warehouse on stilts secretly depicts “Senki,” which is characteristic of shrine architecture (laugh).

Thank you, the “imprint” of the folks at the National Museum of Japanese History is interesting.

I would like to visualize the mental transformation from a hunter-gatherer society to an agrarian society in this area.

I strongly wish to visualize the mental transformation from a hunter-gatherer society to an agrarian society.

I would also like to ask how the reality of these “festivals” is reflected in the Yangtze River estuary, where rice cultivation and agriculture emerged in Asia.

I am also interested in comparing the culture of the Yangtze River estuary, the place where rice farming emerged in Asia.

Posted on 11月 26th, 2022 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 日本社会・文化研究, 歴史探訪

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.