出張の疲労回復にはやっぱり1日くらいの休養が必要で、昨日はなるべくカラダを休めておりました。今回はとくに自宅で寝て起きると、ホテルでの寝起きとはまったく違う「爽快感」を実感させられ、本日で帰宅後2晩目の就寝ー目覚めはさらに体力回復ぶり実感。やっぱり加齢とともに「身の程をわきまえる」ことが大切なのでしょう。

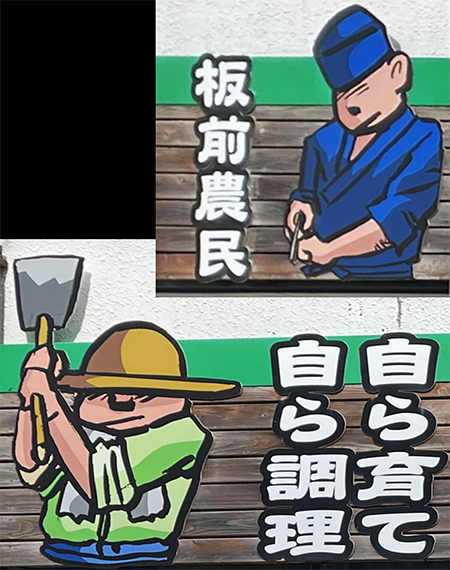

写真は10日前に購入してきた秋の北海道新鮮野菜たち。安定のカボチャはこの値段で煮浸しとか、スープなどに利用して楽しんでおります。先日来ご紹介していた「ソーメンカボチャ」はどっさりとサラダ食材として活用中。これはとにかく調理すること自体が楽しい。加熱して流水で冷ましながら、中身がどんどんとソーメンのようにほぐれていく様子が、なんとも愉快な気持ちにさせてくれる。大根などを線切りにするのは包丁手間がたくさん掛かることを考えると、非常に有用性が高い。食味があっさりしているので「付け野菜」としてはもやし並みの使いやすさかなと思っております。案外ラーメンの付け野菜としてヒットしたもやしのように、工夫次第で大ヒットになる食べ方があるのではないかと思います。料理修業を重ねて、かれの魅力をさらに引き出すメニューを考えたくなっています。

そして全長35cmほどのズッキーニ1本100円也は、ナスとほぼ同様の調理にてたのしく食べさせていただいております。ほんとうにナスと同じような食感でもあり、ほかの食材との相性も抜群にいい。名前がちょっとクセがありますが、食べ方では日本人にぜったいに適していると思うので、洋風から和風の名前に変えれば、もっと消費されるのではないかと思います。

疲労感も一服してきて、またふたたび自分で調理に取り組みたい。ようやく秋風の感じられる北海道。各地の農家から直出品の新鮮野菜たちと出会えると期待しています。そういえば、先週は10kgほどの新鮮タマネギも購入してきて、ジミに食卓ににぎわいを与えてくれている。

今週末にもまだまだ新鮮野菜たちと出会って元気回復したいと考えております。

English version⬇

Enjoying Autumn Vegetables

Fresh vegetables with various characteristics are a source of vitality. Using the right vegetables in the right places stimulates the sense of taste and is very satisfying. It is an enjoyable encounter in autumn. Autumn

I needed a day or so of rest to recover from the fatigue of a business trip, so I rested my body as much as possible yesterday. This time, in particular, when I went to bed at home and woke up, I felt a completely different “refreshed” feeling than when I went to bed and woke up at the hotel. I guess it is important to be aware of one’s own physical condition as one ages.

The photo shows the fresh autumn vegetables I bought 10 days ago in Hokkaido. I am enjoying the stable pumpkin at this price, using it for simmered vegetables and soups. The “somen kabocha” that I have been introducing the other day is now being used in salads. It is fun to cook. As it is heated and cooled under running water, it is a delight to watch the contents unravel like somen noodles. Considering that it takes a lot of time and effort with a knife to cut daikon and other radishes into strips, it is very useful. I think it is as easy to use as bean sprouts as a “garnish vegetable” because of its light taste. Like bean sprouts, which unexpectedly became a hit as a vegetable to add to ramen noodles, I think there are ways to eat it that could become a big hit, depending on one’s ingenuity. With more culinary training, I would like to come up with a menu that brings out even more of his charm.

I am also enjoying a 35-centimeter-long zucchini for 100 yen per piece, which is cooked in much the same way as eggplant. It really has the same texture as an eggplant and goes well with other ingredients. The name is a bit peculiar, but I think it is definitely suitable for Japanese people in the way they eat it, and if the name is changed from Western to Japanese, I think it will be consumed more.

Now that I have a lull in my fatigue, I want to get back to cooking on my own again. Finally, we can feel the autumn breeze in Hokkaido. I expect to see fresh vegetables directly from farmers in various regions. Speaking of which, I bought about 10 kg of fresh onions last week, and they are giving Jimi and me a lot of life at the table.

We hope to meet more fresh vegetables this weekend to restore our energy.

Posted on 10月 2nd, 2024 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: おとこの料理&食 | No Comments »