先週金曜日の握り寿司200カン超で、すっかり元気を使い果たしたようで、週末日曜日はただただひたすら寝ておりました。いちおう午前中は起きていて、美術館に行った後、帰ってきてから昼食を食べた後、午後2時くらいから寝始めて、途中午後7時頃に一度は目覚めたけれど、すぐにまたベッドに入り、深夜1時まで寝ていた・・・。

さすがに握り寿司の大立ち回り、ネタの買い付けから捌き、酢飯づくり、握りと一連の作業量はやはり重い。この10時間近くの睡眠で、ようやく元気回復。あれをやろう、これを片付けようとアタマがようやく動き始めた。

・・・といったところに、パソコンにWEBニュース速報で「バイデン撤退」のニュース。やっぱりかであります。日本の安全保障にとっての最大の根拠・唯一の同盟国の趨勢がどうなっていくのか。リアリズムをしっかり見据える日本人であれば、当然もっとも関心を持つテーマ。速報段階では、バイデンは副大統領の女性カマラ・ハリスの名前を挙げていたということですが、ここから先はまったく読めないのではないだろうか。

たとえバイデンがそのような意向を持ったとしても、民主党としてそれでまとまる、あるいは共和党のトランプに対抗しうるかどうかは別問題。副大統領という存在はそれなりに露出も多いけれど、彼女が大きな存在感を示したことは、ほとんどない。たぶん民主党内で大きな抗争が始まって、代わりの候補が出てくるように思える。さて。

一転して北海道の異常高温状態であります。

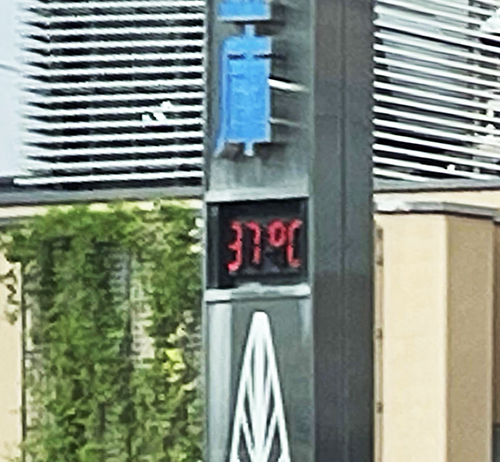

上の写真は夫婦でいつも「大袈裟温度計」と呼んでいる市中の気温計。いつも2−3度程度、暑いときには上振れして、寒いときには下ぶれするヤツなのですが、しかしなんと、37度表示。

いくら大袈裟表示とはいえ、街ゆく人たちも口あんぐり。北海道でまさか生きている内にこんな温度に出くわすことがあるとは思っていませんでした。こういう高温状態では、日中の外出行動などは控える方が得策。わが家は蓄熱性のブロック造なので、家に戻ると一気にクールダウンしてくれる。多くのコンピュータ・プリンター機器などがあるのでエアコンも設置していますが、住宅部分の1階で1台だけときどき運転しています。

高齢者としては、こういう時期は朝夕方だけに散歩運動時間も限定して、安全側の対応で過ごしていきたいです。みなさんもご自愛のほど。

English version

Biden Withdraws from U.S. Presidential Race & Hot Hokkaido

The thermometer in the city read 37 degrees Celsius! I was surprised to see this kind of temperature in Hokkaido while I was still alive. Cool block houses, but we want to stay safe. …

It seems that I had used up all my energy after eating over 200 pieces of nigirizushi last Friday, and I just slept through the weekend Sunday. I was awake in the morning, went to a museum, had lunch when I got back, and started sleeping around 2 p.m. I woke up once around 7 p.m., but went right back to bed and stayed in bed until 1 a.m.

As one would expect from a sushi chef, the workload of buying the ingredients, processing them, making the sushi rice, and nigiri sushi was heavy. After nearly 10 hours of sleep, I finally recovered my energy. My mind finally started to think about what to do and what to put away.

Just as I was about to start, I saw the news of “Biden’s withdrawal” in a web news bulletin on my computer. I knew it. What will become of Japan’s greatest security asset and sole ally? This is a theme that Japanese people with a firm grasp of realism would naturally be most interested in. At the preliminary stage, Biden mentioned the name of the vice presidential woman, Kamala Harris, but I think it is impossible to read anything at all from this point forward.

Even if Biden were willing to do so, whether he could come together on it as a Democrat, or even compete with Trump as a Republican, is another matter. The vice president has a certain amount of exposure, but she has rarely, if ever, had a major presence. It seems to me that perhaps a major infighting will start within the Democratic Party and an alternative candidate will emerge. Well.

For a change, it is abnormally high temperature conditions in Hokkaido.

The photo above is a city-wide thermometer that the couple always calls an “exaggerated thermometer. It is a thermometer that always swings up when it is hot and down when it is cold, but to our surprise, it shows 37 degrees Celsius.

Even though it was an exaggerated display, the people on the street were stunned. I never thought I would encounter such temperatures in my lifetime in Hokkaido. In such high temperatures, it is best to refrain from going outside during the day. Our house is built of heat-storing blocks, so it cools down quickly when we return home. We have air conditioners installed as we have many computer/printer devices, etc., but only one is occasionally run on the first floor of the residential portion of the house.

As an elderly person, I would like to spend these times of the year on the safe side, limiting my walking exercise time only in the morning and evening. I hope you all take care of yourselves.

Posted on 7月 22nd, 2024 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 状況・政治への発言 | No Comments »