息栖神社の境内には「本殿」「拝殿」というような建築はない。代わりに「社殿」が中心的な建築物として建てられている。いわゆる祭神の明示がない。由緒書きには以下の記述。

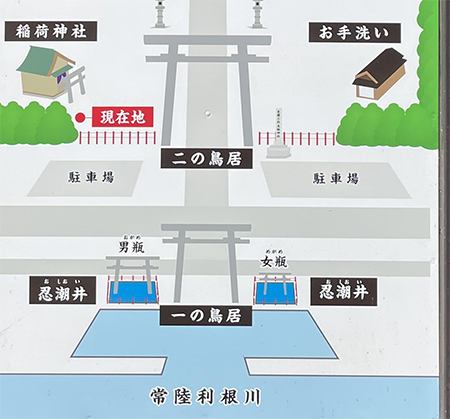

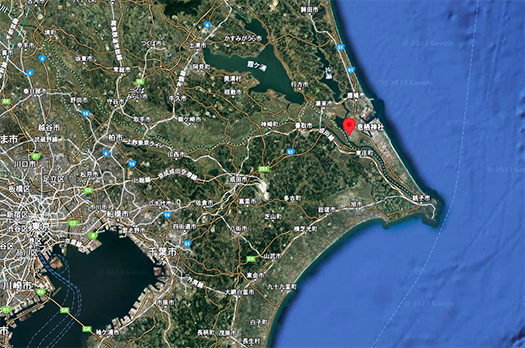

〜息栖神社が最初に置かれたのは現在の日川地区と伝えられており、大同2年(807)に現在地に遷されました。 岐神(くなどのかみ、路の神・井戸の神)、天鳥船神(交通守護の神)に加え、住吉三神(海上守護の神)が祀られています。 息栖神社は鹿島神宮の摂社という位置づけです。〜鹿島神宮の摂社ということで祭神の鎮座する「本殿」は存在しないということ。さらに、

〜御祭神の御神格からして神代時代に鹿島・香取の御祭神に従って東国に至り、鹿島・香取両神宮は其々台地に鎮座するものの、久那斗神(岐神)と天乃鳥船神は海辺の日川(現在の神栖市日川)に姿を留め、やがて応神天皇の御代に神社として祀られたと思われます。〜という記述。

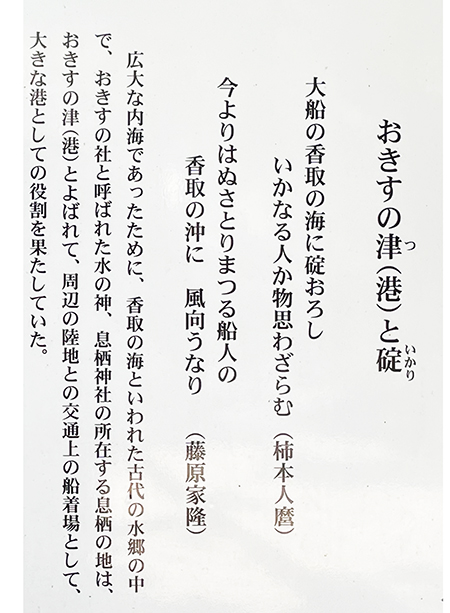

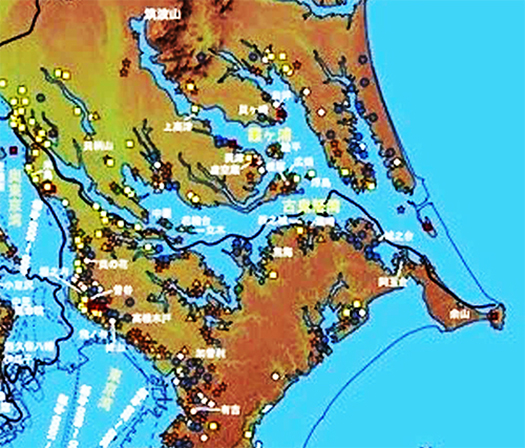

〜かつて鹿島地方の丘陵地南端は今の鹿嶋市国末辺りまでで、やがて沖洲が陸続きとなり幾つかの集落が出来ました。このような中州に鎮座された祠を、大同二(807)年、平城天皇の勅命を受けた藤原内麻呂により現在地の息栖に遷座した。国史書『三代実録』にある「於岐都説神社」が現在の息栖神社です。仁和元年(1120年)の記には「授常陸国 正六位上 於岐都説神従五位下」とあり、於岐都説(おきつせ)は於岐都州(おきつす)であり、沖洲➡息栖になったものであると考えられます。〜

神格自体が特定の人格神ではなく、路の神・井戸の神・交通守護の神というそういった「営為」の守護であるということなのでしょう。常識的な神社信仰とは異質な神格だと言える。

さらに「くなど」という神格をググると「岐の神とは、古より牛馬守護の神、豊穣の神としてはもとより、禊、魔除け、厄除け、道中安全の神として信仰されている。日本の民間信仰において、疫病・災害などをもたらす悪神・悪霊が聚落に入るのを防ぐとされる神である。また、久那土はくなぐ、即ち交合・婚姻を意味するものという説もある。」

息栖神社のいろいろなナゾがようやくにして全貌を見せてくれているように思える。

東国三社として鹿島・香取と同列に位置づけられていながら、モヤがかかったような不鮮明さがぬぐえなかったものが、古代地形としての内海の風景の中で水上交通の最大要衝地であって、その場所自体が「神宿る」とされたけれど、具体的な人格神特定には至らなかったということ。

海外には「マーメイド」という女神が存在する。人魚は女性の頭と上半身、魚の尾を持つ水生生物であり、ヨーロッパ、アジア、アフリカを含む世界中の多くの文化の民間伝承に登場する。

本来であれば、日本の神社信仰でもこういう人格に仮託されるべきだったのかも知れない。

English vrsion⬇

The Shrine of the Unpersonalized God, Ikisu Shrine (5): Exploration of Three Shrines in Eastern Japan – 25

I have been writing and polishing my research on the mysterious shrine. Finally, I came up with a hypothesis. Is it a shrine belief version of the Mermaid legend? The Mermaid Legend.

There is no “main hall” or “hall of worship” within the precincts of the shrine. Instead, a “shrine pavilion” is built as the central structure. There is no indication of the so-called “deities of worship. The history of the shrine includes the following description

〜It is said that the shrine was first located in the present-day Nikkawa area, and was moved to its present location in the 2nd year of the Daido Era (807). The shrine enshrines three deities, Sumiyoshi (guardian of the sea), in addition to Ki (god of paths and wells) and Amatori-Fune (guardian of traffic). The shrine is positioned as a regency shrine of the Kashima Jingu Shrine. 〜The fact that it is a regent shrine of Kashima Jingu Shrine means that there is no “main shrine” where the deities are enshrined. In addition, the shrine does not have a “main hall” where the deities of the shrine reside,

〜The deity of the deity of Kashima and Katori followed the deities of Kashima and Katori to the East during the Kami period, and although both Kashima and Katori shrines were located on the plateau, the deity of Kunato and the deity of Amano-torifune remained at the seashore at Hikawa (present Hikawa, Kamisu City) and were eventually enshrined as a shrine in the reign of the Emperor Ojin. 〜The description of the shrine is “a shrine of the gods of the sea”.

〜In the past, the southern edge of the hills in the Kashima area extended as far as Kunisue, Kashima City, and eventually a sandbar connected to the land and several settlements were established. In 807, Fujiwara no Uchimaro, under the command of Emperor Heijo, relocated the shrine to its present location in the middle of the island. The “Oki-tosetsu Shrine” mentioned in the national history book “Sandai Jitsuroku” is the present-day Ikisu Shrine. In a chronicle of the first year of Ninna (1120), it is written, “授常陸国 正六位上 於岐都説神従五位下,” and it is thought that Okitsuse is 於岐都説, which became Okisu ➡息栖. ~.

The deity itself is not a specific personal deity, but rather a guardian of such “activities” as the god of roads, the god of wells, and the god of traffic protection. It is a deity that is alien to common sense shrine worship.

Furthermore, when I googled the deity “Kudo”, I found that “Ki no Kami has been believed in since ancient times not only as a god of cow and horse protection and fertility, but also as a god of misogi, protection from evil spirits, protection from mischief, and safety on the road. In Japanese folk beliefs, he is said to prevent evil gods and spirits that bring plagues and disasters from entering the village. Some people also believe that kunado means “kunagu,” which means mating or marriage.”

It seems that the various riddles of the Ikisu Shrine have finally been revealed in their entirety.

Although the shrine was ranked with Kashima and Katori as one of the three shrines in the eastern part of the country, it was a strategic point for water traffic in the ancient topography of the inland sea, and although the place itself was considered to be “home to a god,” it was not identified as a specific personal deity.

The goddess “mermaid” exists in other countries. Mermaids are aquatic creatures with a woman’s head, upper body, and fish tail, and appear in the folklore of many cultures around the world, including Europe, Asia, and Africa.

Perhaps they should have been hypothesized as such personalities in Japanese shrine beliefs.

Posted on 8月 30th, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 日本社会・文化研究, 歴史探訪 | No Comments »