昨日は石器時代の父子の黒曜石を巡っての技術伝承のテーマとしたけれど、そのジオラマ展示の相方には、当然、母娘のペアリングでのものがあった。こちらでは、捕獲してその肉を家族で食したあとの獲物動物の「皮革」から衣類を作って行く作業に母娘は一生懸命に取り組んでいた。

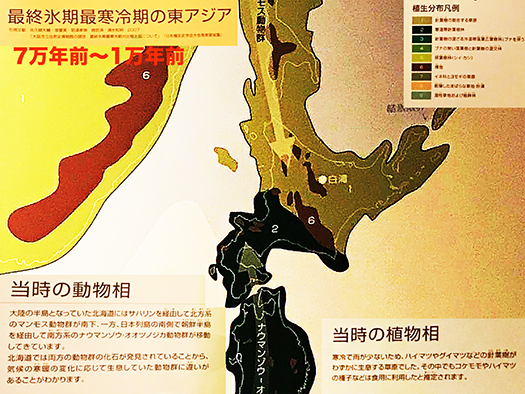

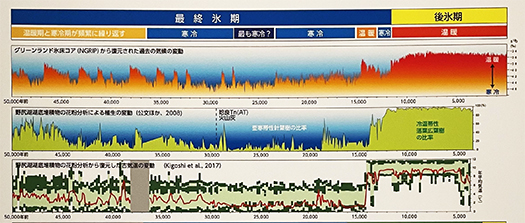

昨日紹介した東京大学文学部教授の佐藤浩幸先生の文章では「この時代は寒冷乾燥を基調としながらも気温は短周期で激しく変動する氷期であったため、人々は植物資源を当てにすることができず、移動を繰り返す中大型動物の狩猟を主要な生業としていた。」と記述がある。

さらに「(縄文時代になると)最後の激しい寒暖が繰り返された晩氷期が終了すると、日本列島を含め地球上は、一斉に安定した温暖期である完新世を迎えた。周囲に本格的な海流が流入したため、列島はこれまでの大陸性気候から海洋性気候に転換し、温暖湿潤な気候のもとで、森林が発達する。」

というように記されている。大ぐくりで見れば、気候変動は常に人類のライフスタイルに深く関わってその文化を規定してきていたことが明確にわかる。とくに日本列島の場合は温暖化に伴って海水面が上昇して完全に島嶼エリアになり、同時に温暖化で周囲の海からの水蒸気が豊富な雨量として降り注ぎ豊かな森林環境が生成された。

逆に言うとそれ以前は大陸的な「乾燥」気候であって、ひたすら動物狩猟だけが生活を支える資源環境であったことが明白。そういった環境で、人類は衣類について文化を発展させた。主に女性たちは動物の皮をなめして、それらを針と糸でつなぎ合わせて作る皮革ファッションに目覚めた。

針は人類の発明の中でももっとも重要なものであったことは間違いがない。寒冷気候の中で人類がほぼ全大陸に進出し得たのは針と衣服のおかげだった。女性こそがもっとも強い。

針のメーカーである萬国製針という会社のHPの紹介文「世界一古い針は、ロシア・アルタイ山脈のデニソワ洞窟で発見されました。この針には糸を通す針穴も開いており、放射性炭素年代測定によって5万年前に作られたことが判明しました。針の長さは7.6㎝で鳥の骨から作られています。この針は、極寒のシベリアで毛皮を縫って衣服を作ることに使われていたと思われます。針の形状も現在私たちが使っている針と全く変わっておりません。」

「キャ!お母さん、針ってすごい。革の服に羽毛も付けられたワ」

「そうね、それつけたらファッション的見栄えも素晴らしい、センスあるわね〜(笑)」

母から娘へ。人類の服への美感の進化は女性の感受性発展によってどんどん加速していったに違いない。

English version⬇

Cold Climate, Leather Fashion, Women and Needlework

The power that has evolved over the ice age is also in the women’s quest for beauty. The power of the human race’s evolution overcoming the glacial cold period is also the quest of women for beauty. …

While yesterday’s theme was about the passing down of skills between a Stone Age father and son over obsidian, the other side of the diorama exhibit was, naturally, a mother-daughter pairing. Here, the mother and daughter were hard at work making clothing from the “hides” of the animals they had captured and eaten as a family.

In the article by Professor Hiroyuki Sato of the University of Tokyo’s Faculty of Letters, which I introduced yesterday, he writes, “This was a glacial period with cold and dry weather, but temperatures fluctuated violently in short cycles, so people could not rely on plant resources and their main occupation was hunting medium and large animals that repeatedly moved. The description goes on to say.

The Jomon Period was the last period of intense cold and warming, and after the Late Glacial Period ended, the Holocene, a stable warm period, came to the Earth, including the Japanese archipelago. With the influx of ocean currents into the surrounding area, the archipelago shifted from a continental climate to an oceanic climate, and forests developed under the warm and humid climate.

This is how it is described in the text. In the big picture, it is clear that climate change has always been deeply related to human lifestyles and has defined their culture. In the case of the Japanese archipelago, in particular, global warming has caused sea level to rise and the islands to become completely island areas, and at the same time, global warming has brought abundant rainfall from the surrounding ocean, creating a rich forest environment.

Conversely, it is clear that before that time, the climate was continental and “arid,” and animal hunting was the only resource environment that supported life. In this environment, humans developed a culture of clothing. Women, in the main, tanned animal skins and joined them together with a needle and thread to create leather fashions.

The needle was undoubtedly the most important of human inventions. It was thanks to the needle and clothing that humans were able to expand to almost every continent in cold climates. Women are the strongest.

The website of a needle manufacturer, Bankoku Seihin, says: “The oldest needle in the world was found in the Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains of Russia. The needle also has a needle hole for thread, and radiocarbon dating has revealed that it was made 50,000 years ago. The needle is 7.6 cm long and made from bird bone. The needle is thought to have been used for sewing fur to make clothing in extremely cold Siberia. The shape of the needle is not at all different from the needles we use today.”

“Kya, Mom, needles are amazing! Mother, needles are amazing. They could even attach feathers to leather clothes.

Yes, it would look great fashion-wise if you put it on, you have good taste.

From mother to daughter. The evolution of humanity’s sense of beauty in clothing must have been accelerated by the development of women’s sensitivity.

Posted on 11月 28th, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 日本社会・文化研究, 歴史探訪 | No Comments »