判官っていう官名からは多くの人は義経のことを想起すると思うけれど、北海道人の場合、もうひとり開拓判官・島義勇のことも想起する。

北海道神宮本殿入り口の正面向かって左手には、かれの銅造、「開拓三神を背負った」姿がある。わたしなどは毎日の散歩コースで見かけ続けているので、ある種、愛情も抱いている(笑)。

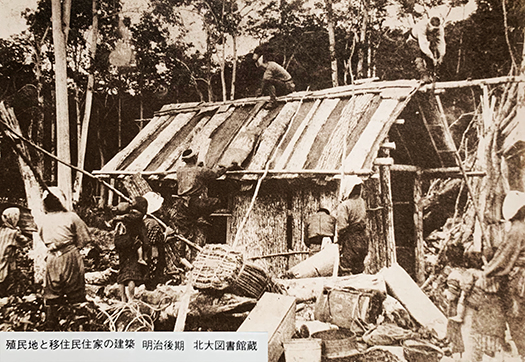

このように引き立てられている反面、かれの北海道での事跡はなんともあっけないもの。明治維新に当たって明治帝はさっそくに北海道開拓の号令を発せられ、その祭政一致の姿勢から「開拓三神」を定められ、その三神をかれ、島義勇に北海道まで持って行かせた。その後の事跡の中で明治帝は、さまざまに問題に直面する島義勇に対して、温情を掛けられているように思える。

あるいは開拓判官として、宮廷で接触された機会があったのかもしれないと思っている。背中に背負わせるというのは、人物に対しての信頼がなければそうはなされないだろう。

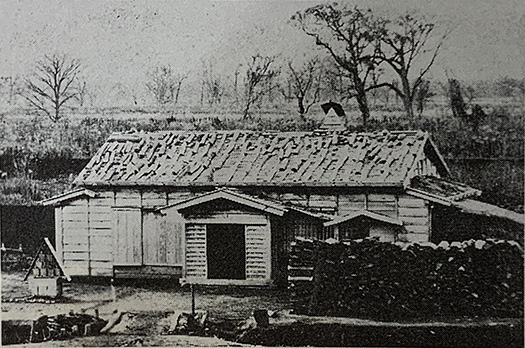

写真は最初期の札幌本府での建築である「林少主典官宅」。住宅領域を北海道で仕事としてきた者としてこういった先人達の息づかいの感じられる小住宅サイズの建築には、ホロッとさせられる。

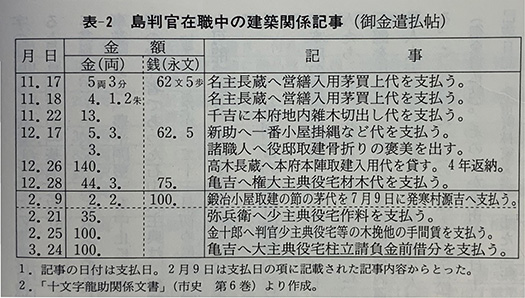

で、その下にはかれのほんの半年あまりの現地・北海道での「官費支出明細」。1870年2/21付けで、この建物の代金支払いがされている。35両という金額でこの写真の小住宅の「役宅作料」が支払われている。幕末には異常な物価上昇が見られ、それがそれまでの「両」から「円」への変換につながった。

幕末の物価では1両は約10,000円とか言われるので、この写真の家は350,000円で建てられたことになる。建材は別支給だとして「作料(工事手間賃)」としてと考えれば、少し整合するかもしれない。こういった記録が残されているのは、北海道人としての身近さに加えてさらに、空気感も見えてきて面白い。

また、この明治2−3年の冬は、たいへん厳しい寒さだったようで、ネコを抱いて寝て寒さをこらえたという記述にも出会って、さらに血肉感がいや増してくる。

一方で、かれ島義勇はやや「直情径行」の節がうかがえる。かれのあまりにも短期間の赴任期間には、当時の蝦夷地の経済主体の中心であった「場所受」層との対立があった。場所受けというのは、松前藩の支配構造としての漁場・浜ごとの権利者たちのことであって、松前藩から札幌本府へと政治支配構造が変化するに際して、島義勇と現地の経済主体層とのあつれきが発生した。なにしろ、いきなりその経済主体権を否定するという施策を打ち出して強硬な反対勢力を生んでしまった。

若い明治帝は、こういう「まっすぐさ」を愛したのかも知れない。紆余曲折があってかれは佐賀の乱の首謀者として斬首されるのだけれど、そうでありながら死後には大赦の対象になって、明治帝も祀られた北海道神宮でいまも無心に帝を慕う姿で飾られている。なにか、伝わってくるものがある。

English version⬇

Yoshiyoshi Shima, “Hokkaido Kaitakushi Hangaku” (Hokkaido Development Judge), appointed in 1869 and dismissed the following year.

The history of Yoshiyuki Shima and his strange fate reveal the Meiji Emperor and his love for Hokkaido. …

The name “hanko” may remind many people of Yoshitsune, but Hokkaido people also think of another pioneer judge, Yoshiyou Shima.

On the left side of the entrance to the main shrine of Hokkaido Jingu, there is a bronze sculpture of him “with the three pioneer gods on his back. Since I keep seeing it on my daily walk, I have a certain affection for it (laugh).

While he is so admired in this way, his history in Hokkaido is rather simple. The Meiji Restoration, which was the first of its kind in Japan, was preceded by the Emperor Meiji’s decree to pioneer Hokkaido, which led to the establishment of the “Three Gods of Kaitakushi (Development)” and the unification of the three gods, which he had Yoshiyou Shima take with him to Hokkaido. In his subsequent history, the Meiji Emperor seems to have shown warmth to Yoshiyou Shima as he faced various problems.

Or, as a pioneer judge, I believe he may have had the opportunity to be in contact with him at court. To put someone on one’s back would not be done so without trust in the person.

The photograph is of the “Hayashi Shao Shuyuan Kangaku Residence,” one of the first buildings constructed in the Sapporo Main Office. As someone who has worked in the residential field in Hokkaido, I am touched by these small house-sized structures that show the breath of our predecessors.

Below is a “government expense statement” dated February 21, 1870, showing the payment of 35 ryo for the small house in the photo. The end of the Edo period saw an extraordinary rise in prices, which led to the conversion from “ryo” to “yen.

Since one ryo is said to cost about 10,000 yen at the end of the Edo period, the house in this photo was built for 350,000 yen. Assuming that the building materials were supplied separately, this may be consistent with the “construction cost. It is interesting that these records are kept not only because they are familiar to the people of Hokkaido, but also because they give us a sense of the atmosphere of the area.

The winter of 1890-1990 seems to have been extremely cold, and we can see that he slept with a cat in his arms to endure the cold, which further increases our sense of his flesh and blood.

On the other hand, Yoshiyuki Shima seems to have been a little more “straightforward” in his actions. During his too short period of service, there was a conflict with the “place-accepting” class, which was the core of the economic entity in Ezo at that time. The “place-recipients” were the holders of rights to fishing grounds and beaches as part of the Matsumae clan’s ruling structure, and as the political ruling structure changed from the Matsumae clan to the Sapporo headquarters, there was a conflict between Shima Yoshiyuu and the local economic entities. In fact, he suddenly proposed a policy of denying the right to economic sovereignty, which generated a strong opposition.

The young Meiji emperor may have loved this kind of “straightforwardness. After all the twists and turns, he was beheaded as the ringleader of the Saga Rebellion, but even so, he was posthumously granted a pardon, and is still displayed at the Hokkaido Shrine, where the Meiji emperor was also enshrined, in a state of unrestrained adoration for the emperor. Something is being conveyed to us.

Posted on 5月 26th, 2024 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 歴史探訪 | No Comments »