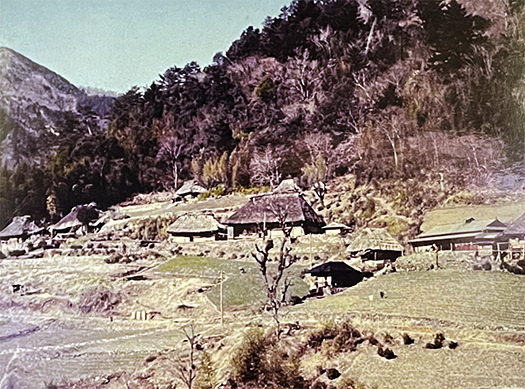

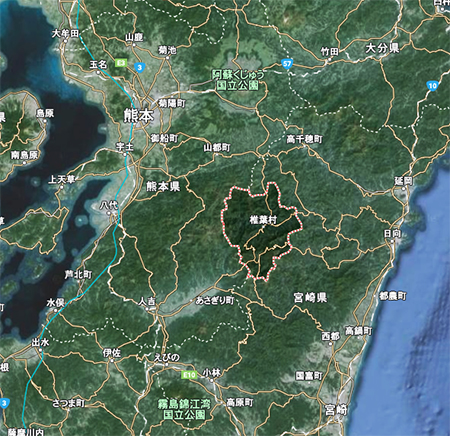

日本三大秘境と言われる四国・祖谷、白川郷とこの日向・椎葉。大阪・豊中の古民家園で突然遭遇していたけれど、やはりほかの民家とは隔絶した「背景事情」が感じられて、深くとらわれてしまった。

現地で見ていたときに日本の古民俗に興味を持っていそうな英米人たちの姿も見かけて、いろいろ話しかけたくなったけれど、片言の会話では語り尽くせないほどの日本史としての奥行きの深さを思ってためらっていた。源平の争乱の歴史など、どういう世界共通理解があり得るのか、測りがたかった(笑)。

自分としてのひとつの非常に大きな体験感として、この秘境の環境の中で800年ほどの時間を生き続けてきた人びとにとっては「敗戦後の時間」ということなのだろう、というものだった。日向・椎葉の人びとにとっては、平家の「わが世」という自分たちのアイデンティティが崩壊し、それでも生き延びるために戦後の生き様をこの長い時間、経過してきたのだろうと思う。かれらにとって、平家の滅亡ということはかくも巨大な重い現実。

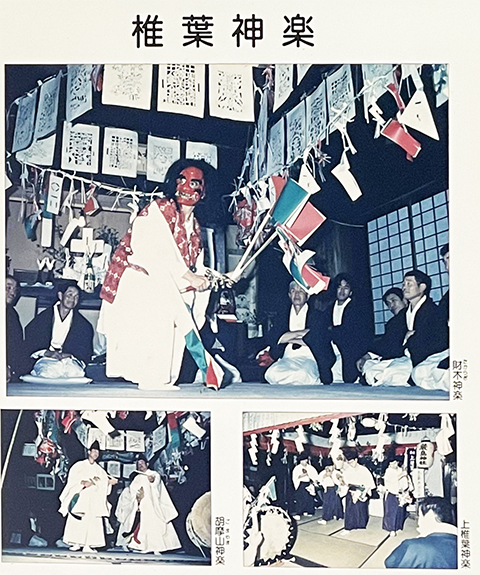

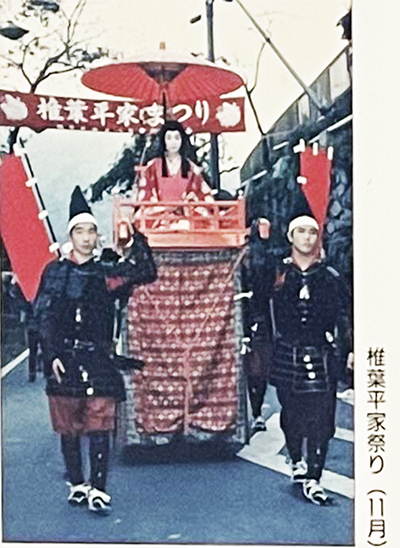

そこから社会・世界との調和を図って生き延びる必要があった。しかし一方できわめて独自な「鶴富姫」伝承など、自分たちの世界での価値感をも守り続けてきた。さらに山里でありながら「陶酔神楽」文化を熟成させて独自発展させていた。

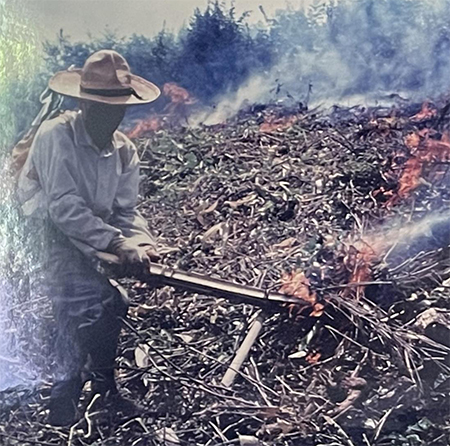

個人的には、この平家落人集落の「経済構造」を考えていて、いろいろな書物を見ているうちに、この列島社会での基底文化としての「狩猟採集」ライフスタイルというものに深く気付かされた。司馬遼太郎の「街道をゆく」シリーズをなにげに平行読書していたら、大阪城攻めに動員された紀伊の「十津川」の人びとについての記述箇所に遭遇した。そこではそれまでほぼまったく「水田耕作」を行わなかったかの地域の人びとが、生業としての「弓矢」の術を軍事動員されていた記述。平家の落人の基本的な生き延び方の疑問が氷解した。

わたし自身はいわゆる「戦後」の時間のなかだけを生きてきた。もうすでに80年以上こうした時間が経過しているけれど、日本社会というのはそういうなかでの「生き延び方」について、非常に柔軟な社会であるのかも知れない。ちょうど江戸幕府体制がながく存続したように。

結局,再度「黒船」のような外圧が来襲することによって、変化は根底的に訪れるものなのだろう。それが危機として直面しないように祈りたい。

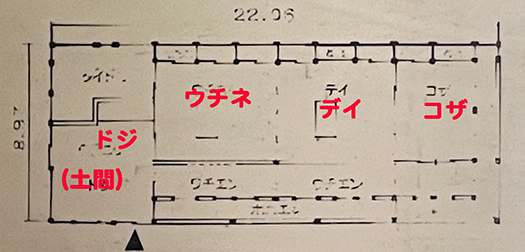

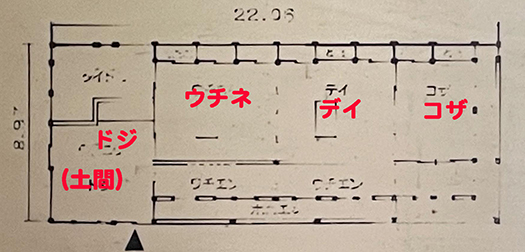

日向・椎葉の家というのは思いもかけず、そんなことにまでわたしを誘ってくれる機縁になっていた。住空間というものは、そこで生きた人間と社会を抱擁する存在なので、その空気感は非常に重大な気付きにもなっていくのだと今更ながら気付かされた。 <この項終了>

English version⬇

The 800-year-old “postwar” village of Hyuga, a Heike Orachi-jin Village-5

The Genpei uprising and World War II. The experienced knowledge of the Orachi-nin community after the war echoes like a distant thunderbolt. The village is a place where people can live and work together.

Iya, Shikoku, Shirakawa-go, and Shiiba, Hyuga, are said to be the three most mysterious places in Japan. I had suddenly encountered them at an old folk house garden in Toyonaka, Osaka, but I was still deeply captivated by the sense of “background circumstances” that separated them from other folk houses.

When I was there, I saw some Anglo-Americans who seemed to be interested in old folklore, and I wanted to talk to them, but I was hesitant because of the depth of Japanese history, which is too deep to be discussed in a one-word conversation. It was hard to gauge what kind of universal understanding of the history of the Genpei wars, for example, was possible (laugh).

One of my very big impressions was that for the people who have been living in this unexplored environment for 800 years or so, it must be “time after the defeat. For the people of Hyuga and Shiiba, their identity as the “our world” of the Heike clan has collapsed, and they must have been living a postwar lifestyle for such a long time in order to survive. For them, the destruction of the Heike clan is a huge and heavy reality.

They had to survive in harmony with society and the world. At the same time, however, they have also maintained their sense of values in their own world, such as the extremely unique “Tsurutohime” tradition. Furthermore, despite being a mountain village, they had matured and developed their own “euphoric kagura” culture.

Personally, as I was thinking about the “economic structure” of this Heike Orachi-jin settlement, I became deeply aware of the “hunter-gatherer” lifestyle as the base culture of this archipelago society as I looked at various books. While casually reading Ryotaro Shiba’s “Kaido yuku” series in parallel, I came across a passage describing the “Totsukawa” people of Kii who were mobilized to attack Osaka Castle. In the article, the people of the region, who until then had not practiced rice paddy cultivation at all, were mobilized by the military to use the art of bow and arrow as a means of livelihood. The question of the basic survival of the fallen Heike people was cleared up.

I myself have lived only in the so-called “postwar” period. Although more than 80 years have already passed, Japanese society may be a very flexible society in terms of how to “survive” in such a situation. Just as the Edo shogunate system survived for a long time.

In the end, change will come fundamentally when external pressure like the “Black Ships” strikes again. I pray that this will not be faced as a crisis.

The house in Hyuga/Shiiba unexpectedly became an opportunity to invite me to such a thing. I now realize that the atmosphere of a dwelling space is a very important reminder that it embraces the people and society that live there. <End of this section>

Posted on 6月 5th, 2024 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 日本社会・文化研究 | No Comments »