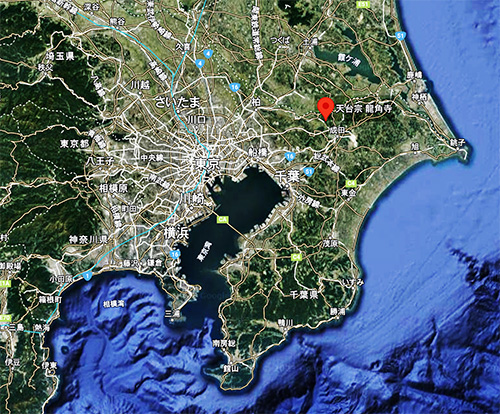

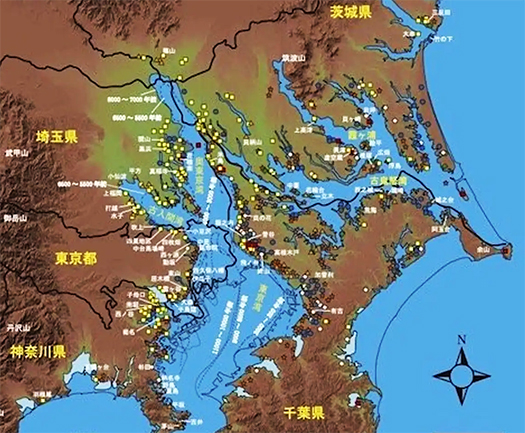

この龍角寺のある周辺は関東でも有数の古墳集積地域。古墳時代後期(6世紀)から終末期(7世紀)の古墳群。現在確認されている古墳の総数は115基。関東では上野(こうづけ)を拠点とした上毛野氏勢力が有力とされるけれど、この龍角寺周辺もその集積ぶりでは圧倒的な大規模古墳群。印旛沼に面する台地縁辺部に6世紀の円墳や前方後円墳が並んでいる。

関東有数の古民家園・千葉県立「房総のむら」敷地内にあって多くの古墳が良好に保存されている。指定範囲内には93基の古墳が含まれるとのこと。

この古墳群は、近傍に所在する白鳳期創建の龍角寺との密接な関連が想定される。この古墳群と周辺遺跡の背景には、印旛沼北岸から香取海南岸に本拠を置いた一豪族が、大和王権の東国支配が確立されていく過程で中央王権の代行者としての地位を獲得し、律令国家成立後も国家機構の一翼を担う在地勢力となったことが考えられるのですね。

写真は2022年10月の早稲田大学會津八一記念博物館での「下総龍角寺再考」シンポ資料より。古墳は龍角寺古墳群101号の外観。

全国で古墳文化はある段階から急減していくけれど、それは多く「寺院建築」に置き換わっていった王権勢力の権威文化の移り変わりを表しているのだと思える。それは同時に八百万の神が、神宿る自然を依り代としてきたのに対して、対比的だと思える。

列島の自然環境に帰依する自然崇拝系の「宗教」といえる八百万の「威信建築」としては自然改造の古墳づくりとその形状を権力象徴としたのだろうが、その次の新時代として仏教寺院とその建築伽藍様式が権威の象徴に変化していったと言える。

そういう権威付けのシンボルとしては、本尊の仏像とその表情ぶりはそれまでの古墳の形状以上にわかりやすく権威の裏付けを「見える化」させたものと推定できる。そしてそれまでの自然崇拝という宗教性から、仏教思想という人間化された宗教が導入された。

具体的な表情を持った「神性」というものに縄文由来の人びとがどのように反応して、それを受容していったのか、想像力が刺激される。それまでは地域王権の具体的な表徴としては古墳を見せていたものが、ある時期から突然、仏教伽藍にそれが変わり、さらに具体的な人間の表情を持った「みほとけ」が出現してきたワケだ。

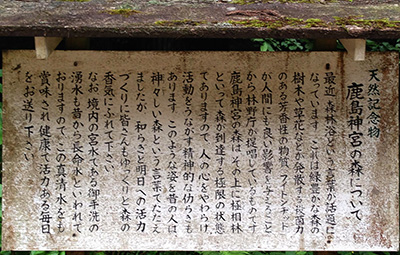

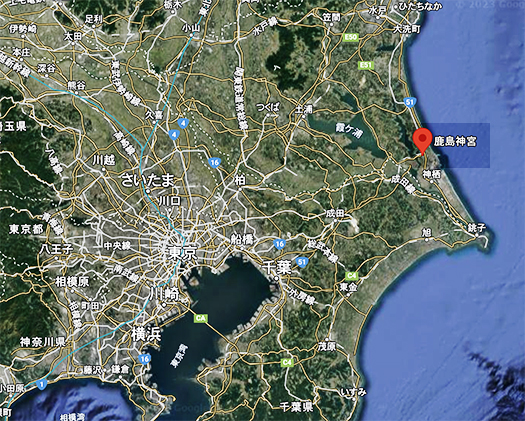

現実の日本史で展開していったのは、八百万と仏教は共生的に併存していったということ。大陸的な傾向では二者択一的に偏っていくものが、日本では併存していった。この関東東部では、鹿島神宮や香取神宮と古墳群、そして龍角寺という宗教性がそれぞれで併存していった。後の世の成田山新勝寺もしかり。

王権権力と宗教性との絡み合いが、複雑な過程を辿ったということなのでしょうね。

English version⬇

From Kofun Tumulus to Buddhist Temple Architecture, Ryukakuji Temple (3): Exploring the Three Shrines of Eastern Japan – 10

The form of manifestation of power changed from ancient burial mounds to Buddhist temples. The area around Ryukakuji Temple is a pinnacle of this ancient period. The temple is located in the vicinity of Ryukaku-ji Temple.

The area around the Ryukakuji Temple is one of the most concentrated areas of kofun tumuli in the Kanto region. The tombs date from the late Kofun period (6th century) to the end of the Kofun period (7th century). The total number of confirmed kofun tumuli is currently 115. In the Kanto region, the Kamimono clan, based in Kozuke, is the dominant force, but the area around Ryukakuji Temple is also by far the largest tumulus cluster in the Kanto region. On the edge of the plateau facing Obanuma, there is a row of 6th-century round mounds and posterior-rectangular mounds.

Many of the tombs are well preserved within the grounds of the Chiba Prefectural “Boso no Mura,” one of the largest old private gardens in the Kanto region. The designated area includes 93 burial mounds.

It is assumed that this tumulus group is closely related to the nearby Ryukakuji Temple, which was founded in the Hakuho Period. So the background of this kofun tumulus group and the surrounding ruins suggests that a powerful tribe based on the northern coast of the Inba Marsh to the southern coast of the Katori Sea acquired a position as an agent of the central royal power in the process of establishing the Yamato royal power’s rule in the East, and became a local power that played a part in the state structure after the Ritsuryo state was established.

The photo is from the “Reconsidering Shimousa Ryukakuji Temple” symposium held at the Aizu Yaichi Memorial Museum of Waseda University in October 2022. The tumulus is the exterior of the Ryukakuji Tumulus Group 101.

The tumulus culture declined sharply after a certain stage in the history of Japan, but I believe that this represents a shift in the culture of authority of the royal power, which was replaced by “temple architecture” in many cases. At the same time, this is in contrast to the 8 million deities who have taken refuge in the nature in which they dwell.

The “prestige architecture” of the eight million nature-worshipping “religions” that took refuge in the natural environment of the archipelago may have been the mound structures modified by nature and their shapes as symbols of authority, but in the next new era, Buddhist temples and their architectural temple styles became symbols of authority.

As such symbols of authority, the main Buddha image and its facial expression are more easily understood than the shape of the kofun tumulus, and it can be assumed that they “visualized” the support of authority. The religious nature of nature worship that had existed up to that point was replaced by the humanized religion of Buddhist thought.

It is stimulating to the imagination to see how people of Jomon origin reacted to and accepted the “divinity” that had a concrete expression. The Jomon had previously displayed kofun as a concrete expression of local kingship, but at some point in history, this was suddenly replaced by Buddhist monasteries, and “mihotoke” appeared with a more concrete human expression.

What has developed in actual Japanese history is the symbiotic coexistence of the eight millions and Buddhism. What would have been a continental trend toward a bias toward one or the other, in Japan they coexisted. In the eastern part of the Kanto region, the Kashima Shrine, the Katori Shrine, the ancient burial mounds, and the Ryukakuji Temple were all religious entities that coexisted with each other. The same is true of the later Naritasan Shinsho-ji Temple.

It must be said that the intertwining of royal power and religiosity was a complicated process.

Posted on 8月 14th, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 日本社会・文化研究, 歴史探訪 | No Comments »