旧蓮見家住宅はさいたま市緑区井沼方、大宮台地の南端部、見沼の低地から入り込む谷に突き出た舌状台地上に所在していた。1730年当時開拓された「見沼たんぼ」のなかに「蓮見新田」もある。この地域は幕府直轄領であり「村高」は66石という記録がある。この一家が生産する米は成人66人が1年間に消費する量に相当するという記載とのこと。

建物の建築年代を直接示すものはなく明らかではないが、構造手法から見て、江戸時代中期18世紀の前半、ちょうど1730年という年代時期に相当すると推定。そうすると約300年前となるか。桁行16.75メートル、梁間5.4メートルの寄棟造り、茅葺屋根の建物。たぶん新田開発を進めながらその農作業にも従事していた、その生産拠点としてやや高台の立地に建てられ、土地を管理していたのでしょう。関東のような平野部でも自然地形での高低差はあり、低地は水利を得やすく水田造営に適していたでしょうが、そのことは水害被害に遭いやすいということでもあり、居住家屋としては農地に適さない高台を選択したものでしょう。そういう土地利用は関東でよく見かける。

内部は向かって右に間口の半分以上の土間を取り、土間に沿って梁間いっぱいに板の間のヘヤ、その上手にオクと、その裏側にナンドを配している。いわゆる三室広間型の間取り。ヘヤには囲炉裏を設け、囲炉裏に接し土間側に板敷きの床を張り出していて、このヘヤ後方には戸棚を造りつけている。

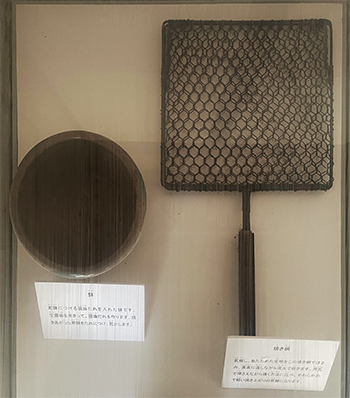

この建物の特徴として、南面するヘヤにはシシマド(格子窓)があること、柱は1間ごとに直接礎石の上に立つこと、大黒柱は細く杉材が使われている等があげられる。

シシマド・格子窓は「シシよけ窓」などと呼ばれており、イノシシやオオカミなどの獣の侵入を防ぐためのものだと言われて関東・中部地方に多く見られるという。逆に言うと家屋に対してそういった動物たちが進入を試みることがあったということ。

上の写真では外観の中央に格子窓がある。内観側の様子をあわせて見ていただきたい。内部側からはあんまり格子の存在は感じない。たんなる「明かり窓」のように思える。

やや高台の住居という条件では当然周囲は森に囲まれた環境になり、そういった獸たちが旺盛にテリトリーを作っていたのでしょう。現代北海道ではふたたびヒグマの害が増加してきているけれど、江戸期の関東開拓進行期でも、そういう用心が建築的にまで計られていた。いかにも「開発農家」的な雰囲気が色濃く感じられる。

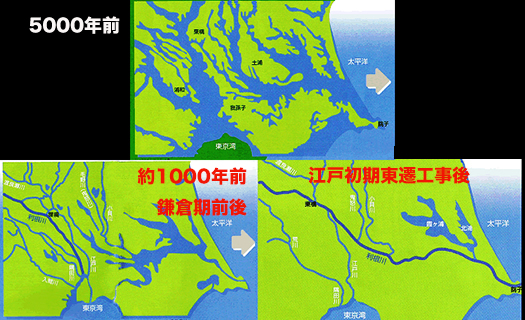

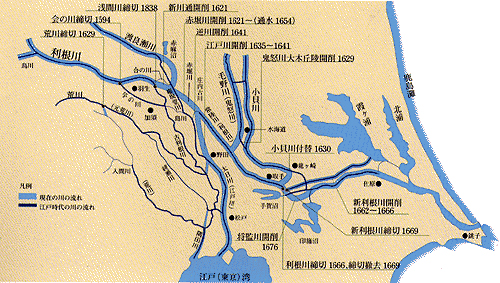

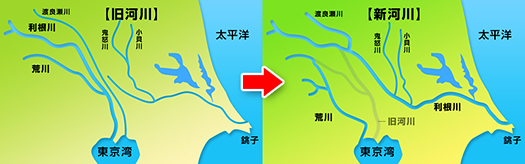

こういった関東での再開発が、明治以降北海道の「開拓農家」への民族的導火線になっていったというようにも類推が働いてくる。利根川東遷などの大規模自然改造・再開発が江戸期を通じて行われた、そういう意味では関東は「新開地」そのものだったのか。家康に捧げられた「東照大権現」という名前の意味があらためて興味深く想起される。

English version⬇

The God of Kanto’s Redevelopment, Tosateru Daigongen? Development farmers in Urawa-3

The “Shishimado,” a lattice window and a defensive device against wild boars and wolves, tells the story of the “newly developed land. Is the precedent of Hokkaido development the Kanto redevelopment? …

The former Hasumi family residence was located in Inumakata, Midori-ku, Saitama City, on the southern edge of the Omiya Plateau, on a tongue-shaped plateau that juts out into the valley that enters from the Minuma lowlands. This area was under the direct control of the shogunate, and the “village height” was recorded as 66 koku. It is said that the amount of rice produced by a family is equivalent to the amount consumed by 66 adults in a year.

Although there is no direct evidence of the building’s construction date, it is estimated to be in the first half of the 18th century during the middle of the Edo period (1730), which would make it approximately 300 years old. That would make it approximately 300 years old. It is a hipped-roof building with a thatched roof, 16.75 meters long and 5.4 meters beam-to-beam. It was probably built on a slightly elevated site as a production center for the development of new rice paddies and farming activities, and was probably used to manage the land. Even in the plains of the Kanto region, there are differences in elevation in the natural topography, and while lowlands are probably more suitable for paddy field development due to the ease of obtaining water, this also means that they are more susceptible to flood damage, so they probably chose higher ground for their residences, which is not suitable for farming. Such land use is often seen in the Kanto region.

The interior has an earthen floor more than half the width of the frontage on the right, a heya (a wooden floor) between the beams along the earthen floor, an oku (a wooden floor) above the heya, and a nando (a wooden floor) behind the heya. The floor plan is what is called a “three-room, wide-room” type. The hearth is set in the hearth, and the earthen floor is covered with wooden planks.

The only tatami-matted oku has an alcove, a butsudan (Buddhist altar), and a cupboard for decoration in the tatami room.

Other features of this building include shishimado (lattice window) on the south-facing heya, pillars standing directly on the foundation stone every 1 ken, and the daikoku-bashira (main pillar) made of thin cedar wood.

Shishimado or lattice windows are called “shishimado-yado” (meaning “window to keep out wild boars and wolves”), and are said to be common in the Kanto and Chubu regions of Japan. Conversely, such animals sometimes attempted to enter the house.

In the photo above, there is a lattice window in the center of the exterior. Please take a look at the interior as well. From the interior, the latticework is not so obvious. It seems to be just a “light window.

The house is located on a slightly elevated plateau and is naturally surrounded by forest, so these animals must have been actively establishing their territory. Even in the Edo period (1603-1868), when the Kanto region was being pioneered, such precautions were taken even architecturally. The atmosphere of a “development farmer” is strongly felt.

It is analogous to the way that the redevelopment of the Kanto region became a national focal point for Hokkaido’s “pioneer farmers” after the Meiji period. In this sense, the Kanto region may have been a “newly developed land” itself. The meaning of the name “Tosateru Daigongen,” which was dedicated to Ieyasu, is once again interestingly recalled.

Posted on 7月 21st, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 住宅マーケティング, 日本社会・文化研究 | No Comments »