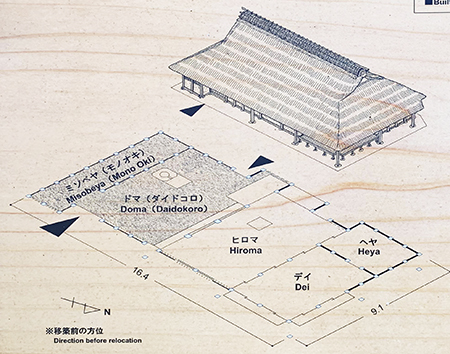

沖縄の古民家でも「竹の床」というものを経験したことがある。

6月末くらいの時期に訪問したので、厚い屋根の萱葺きで直射日光が抑えられ

そして相対的に温度上昇が低減されている床土間との空隙に空気対流が起こって

徐々に発汗が抑えられていく感覚を抱いた。

現代ではエアコン機械利用になる気候対応を、建築として工夫している。

北海道は寒さへの対応での技術進化だけれど、蒸暑気候では

こういった知恵の対応もあるのかと知らされた。

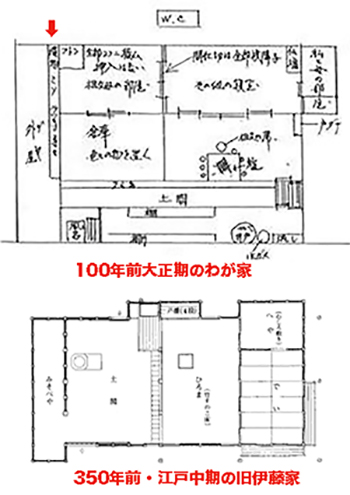

そういった経験があったので、この関東神奈川県川崎の北部、多摩と接する地域の

古民家でも竹の床の文化があるのかと素直に受容していた。

ところが、川崎市教育委員会のこの建物の「ガイダンス」を読むと、

木の板材による板敷きと比べてコストが低廉で済むというポイントから

いわばコスパ優先での「庶民住宅」の床というように案内されていた。

しかし、そういった説明ではもっと厳しい生活条件下の五箇山の家などで

板敷きが敷き詰められていることと整合しないように思われる。

この家では不揃いな柱や梁が多用され、土塗り壁仕上げが目立っている。

五箇山の家では壁にも「板倉」工法で木の板が壁を構成していた。

江戸期、木材入手はどのようであったかの方に興味を抱く。

「ガイダンス」では無意識のうちに建材流通が農家住宅などにも普及していたという

そういった現代常識的な前提があるのではないだろうか。

たしかに江戸期には「木場」とかの地名が今に残るように、

あるいは紀伊国屋文左衛門の大成功などの逸話のように都市部建築は

木材流通が前提になっていただろうけれど、やや鄙の場所であれば、

地元の山から材料を切り出した方が巨大な「輸送コスト」が抑えられただろう。

五箇山は現金収入の少ない地域だけれど、豊富に木材資源はあり、

同時に飛騨の匠という地域伝統としての木工技術集積も地域に存在した。

このような条件の結果と考える方が蓋然性が高いのではないか。

この川崎市北部の農家では、近在の森から木を切り出したけれど、

それらは曲がりと太さの一定しない木材が多くを占めていた。

また、木材の供給可能絶対量は圧倒的に不足していた。

そこでやむなく、木の板敷きを諦めいわば代用として竹の床に向かったのではないか。

その設計構想時に、沖縄などの竹床文化が知識としてあったのではないか。

地域住文化・材料と建築技術の相関関係に置いて理解すべきではないかと思う。

その上でなお、住宅性能的な面からもメリットが高かったと理解した方が

より現実に近いように思え、しっくりくるのではないか。

関東も蒸暑の夏は厳しいし、梅雨時期のジメジメ感もハンパない。

たとえ冬期の寒さの厳しさを考慮しても、

それは縁側での日射輻射をゲットして「やり過ごして」夏期対策としたのではないか。

写真は以前、夏期と冬期の両時期に撮影したものがあったので

両方を併置してみた。冬には竹の床面にムシロの敷物を掛けて

いわばカーペットとして利用して寒さへの対策とされていた様子がわかる。

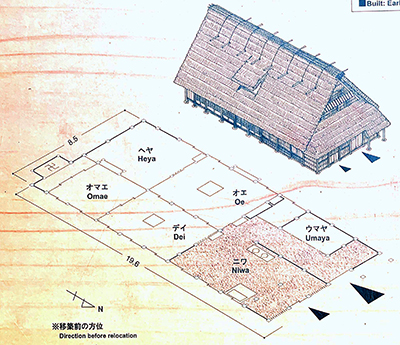

この旧伊藤家では最上級の座敷は畳12枚が敷き込まれている一方、

面積の1/3以上は土間が占めている。

残余の、というか、普段の生活領域はおおむねこの竹敷きの間ということになる。

畳を敷き込むというのは、農家でもあり自作したものか、

近在の畳職人から購入したものか、どちらも考えられるけれど、さて。

English version⬇

[Culture of laying bamboo on the floor / Good Japanese house ㉑-4]

I have also experienced a “bamboo floor” in an old Okinawan house.

Since I visited around the end of June, the thatched roof has a thick roof to prevent direct sunlight.

And air convection occurs in the gap between the floor soil where the temperature rise is relatively reduced.

I felt that sweating was gradually suppressed.

In modern times, we are devising a climate-friendly building that uses air-conditioning machines.

Hokkaido is a technological evolution in response to the cold, but in a hot and humid climate

I was informed that there was a response to this kind of wisdom.

Because I had such an experience, in the northern part of Kawasaki, Kanto Kanagawa Prefecture, in the area that borders Tama

I honestly accepted that even old folk houses had a culture of bamboo floors.

However, when I read the “guidance” of this building of the Kawasaki City Board of Education,

From the point that the cost is cheaper than the wooden boarding

So to speak, it was guided as the floor of a “common house” with priority given to cospa.

However, in such an explanation, at a house in Gokayama under more severe living conditions, etc.

It does not seem to be consistent with the paving of the planks.

Ragged columns and beams are often used in this house, and the plastered wall finish is conspicuous.

At Gokayama’s house, wooden boards were also used to form the walls using the “Itakura” method.

I am interested in how the timber was obtained during the Edo period.

According to the “guidance,” the distribution of building materials was unknowingly widespread in farm houses.

I think there is such a modern common sense premise.

Certainly, in the Edo period, place names such as “Kiba” still remain.

Or, like the anecdote of Kinokuniya Bunzaemon’s great success, urban architecture

It would have been supposed to be timber distribution, but if it’s a little rural place,

Cutting out the material from the local mountains would have reduced the huge “transportation costs”.

Gokayama is an area with low cash income, but it has abundant timber resources,

At the same time, there was also an accumulation of woodworking techniques as a local tradition of Hida Takumi.

It is more likely that it is the result of such conditions.

At this farmhouse in the northern part of Kawasaki City, a tree was cut out from a nearby forest,

They were dominated by wood with inconsistent bends and thickness.

In addition, the absolute amount of wood that can be supplied was overwhelmingly insufficient.

So I had no choice but to give up on the wooden board and head for the bamboo floor as a substitute.

At the time of the design concept, I think there was knowledge of bamboo floor culture such as Okinawa.

I think it should be understood in terms of the correlation between local living culture / materials and building technology.

On top of that, it is better to understand that the merit was also high in terms of housing performance.

It seems to be closer to reality, and it seems to fit nicely.

In the Kanto region, the hot and humid summers are harsh, and there is no sense of dullness during the rainy season.

Even considering the severity of the cold in winter

Perhaps it was a summer measure by getting the solar radiation on the porch and “overtaking” it.

I used to take pictures in both summer and winter, so

I tried to juxtapose both. In winter, hang a straw mat on the bamboo floor

You can see how it was used as a carpet to prevent the cold.

In this former Ito family, the finest tatami mats are laid with 12 tatami mats, while

The soil occupies more than 1/3 of the area.

The rest, or rather, the usual living area is mostly the bamboo floor.

Is it a farmer’s own work to lay tatami mats?

I can think of either the one I bought from a tatami mat craftsman nearby, but by the way.

Posted on 2月 7th, 2021 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 住宅マーケティング, 日本社会・文化研究 | No Comments »