この草戸千軒にほど近い位置に「明王院」「草戸稲荷神社」社寺が有名な古刹。明王院の五重塔も、神社も高層建築でまるでビルとも思える。これらは当時の工人たちの明白な技術の結晶だろう。

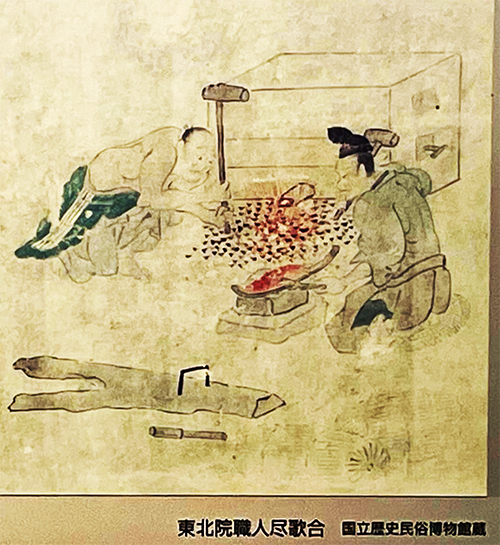

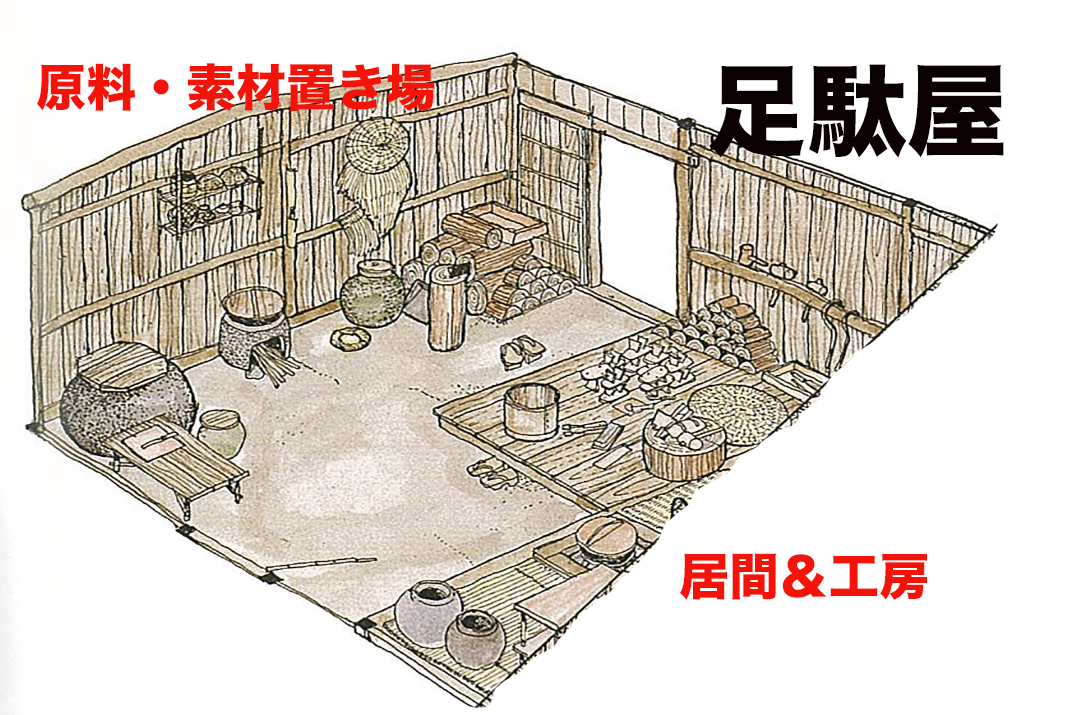

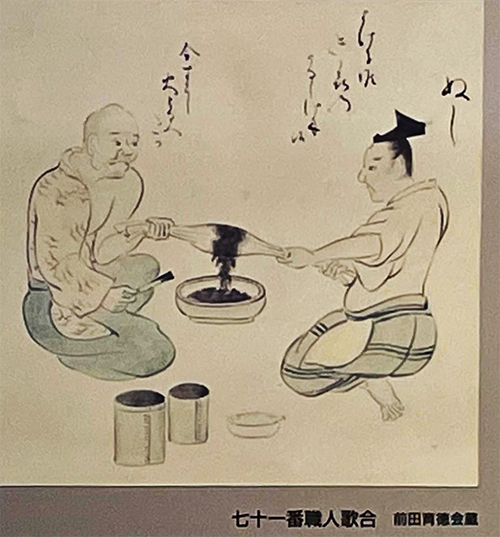

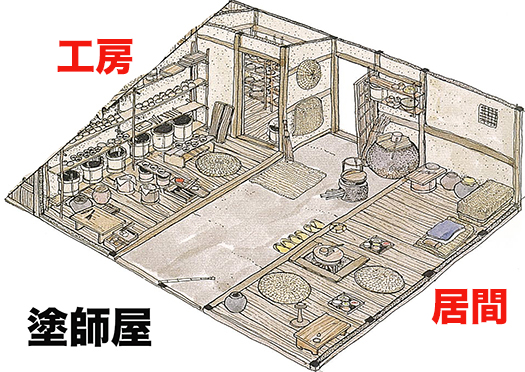

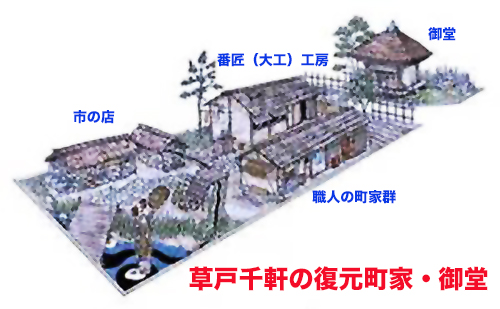

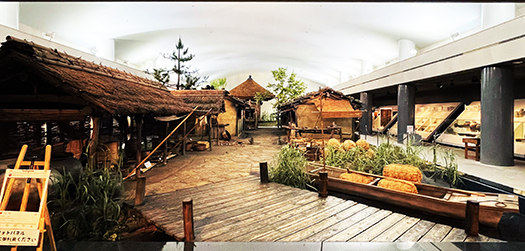

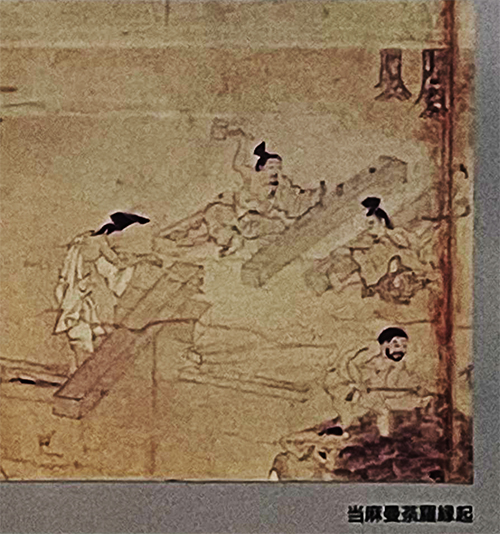

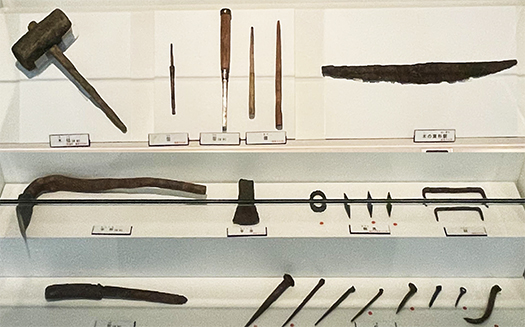

日本民族にとってのもっとも身近な「地域製造業」としての大型木造建築集団。この草戸千軒ミュージアム展示では「番匠」という呼称で加工現場「作事場」が復元展示されていた。

現代ではこの身近な建築衆のことを大工さんという言い方をする。しかし歴史的には「大工」というのは、木造職人さんたちを束ねる「棟梁」的な立場を司っていた人物のことを尊称した名前。そういった専門職としてはむしろ「番匠」の方が中世社会としてはふさわしい名前と思える。

こういった建築技術集団は日本列島社会では古代から存在したことが間違いないだろう。そうでなければ三内丸山とか、出雲大社社殿、吉野ヶ里遺跡などの大型木造建築の成立は考えられない。とくに出雲大社の地上48m相当といわれた往古の超高層木造建築は達成し得なかっただろう。出雲の社殿の「伝承」としてこの超高層建築は「神話」に属すると思われていたものが、実際に巨大な心柱が、巨木3本を金輪で構造補強としてまとめられ締め上げられて出土するというに至って、現実だったことが確定した。

そういった古代からの木造技術伝承は社会に深く根ざしてあり続けてきたのだろう。一方で、世界最古の建築「会社」金剛組は現代まで1450年以上存続し続けてきている。この金剛組は聖徳太子の仏教導入政策の担い手、寺院建築の専門家として百済から来日して、そのまま宮大工として、寺院建築の延命補修の専門職として長く存続してきた。産業としての建設業は社寺仏閣という「公共事業」の担い手という存在として日本社会で永続してきたのだ。こういう技術伝承は日本社会の屋台骨資産なのだと強く思う。

草戸稲荷神社は平安時代の807年創建、一方の明王院は大同2年(807年)弘法大師の開基と伝えられている。ということはこの2つはほぼ同時期に建築工事されたことになる。創建時期のことを考えればたぶん真言宗大覚寺派の古刹である明王院が主体工事だったことが想像できる。

これら古刹の「下町」のような芦田川の中州に草戸千軒は町屋として成立した。

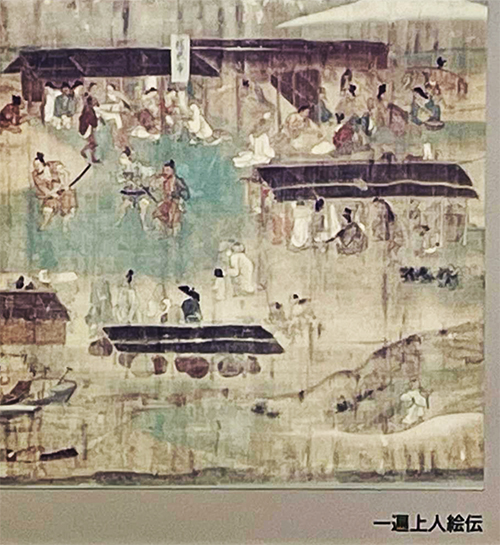

このふたつの大工事が草戸千軒という中世都市生成・維持にとって決定的な要因だったことは疑いがない。社寺建築に関わるあらゆる職方がこの都市に集中して、いかにも「門前市」をなす景況を生み出していったことは確実。ひとつの大工事事業があらゆる産業を成立させていくことは自明。いろいろな関連工事の職人たちが連携し合っていくときに近接して住むことは合理性がきわめて高い。このような社寺建築事業が歴史的に継続して営まれてきたことが、日本の産業史の骨格をも形成したと思える。

English version⬇

The “Bansho” domestic industry group created by shrine and temple architecture – Kusado-Senken 2023 Revisited-9

The Izumo-taisha shrine pavilion, an ancient 48-meter large wooden structure, was considered a myth, but it has been proven to be a real structure. Visualization of the social “economic” function of shrine and temple architecture. …

Now, finally, the construction group as the most familiar “local manufacturing industry” for the Japanese people. In this Kusado-Senken Museum exhibit, a restored “sakugijo,” a processing site, was displayed under the name of “bansho.

Today, the term “carpenter” is used to refer to this familiar group of builders. Historically, however, “carpenter” was a respectful name for a person who was in charge of a “master carpenter,” a position that united wooden craftsmen. As such a profession, “bansho” seems a more appropriate name for medieval society.

There is no doubt that such a group of building techniques existed in the Japanese archipelago since ancient times. Otherwise, it is inconceivable that large wooden structures such as Sannai-Maruyama, the Izumo-taisha shrine pavilions, and the Yoshinogari ruins could have been constructed. In particular, the Izumo-taisha shrine, which is said to be equivalent to 48 m above the ground, could not have been built with the super high-rise wooden structures of the past. What had been thought to be a “myth” of Izumo’s shrine buildings was confirmed to be a reality when three huge pillars were actually excavated from three huge trees that were tightened together with a metal ring for structural reinforcement.

Such ancient traditions of wooden construction technology must have been deeply rooted in society. On the other hand, the world’s oldest architectural “company,” Kongogumi, has continued to exist for more than 1,450 years until the present day. The Kongo-gumi came to Japan from Baekje as temple construction specialists who were instrumental in Prince Shotoku’s policy of introducing Buddhism. The construction industry as an industry has persisted in Japanese society as a bearer of “public works” such as shrines, temples, and Buddhist temples. I strongly believe that the transmission of these skills is a fundamental asset of Japanese society.

Not far from this Kusado-Senken are the famous old temples and shrines of “Kusado Inari Shrine” and “Meio-in Temple” (in order of photo). The shrine is a high-rise structure that looks like a building, and the pagoda of Meio-in Temple is the fruit of the skill of the craftsmen of that time.

Kusado-Senken was established as a townhouse in the middle of the Ashida River, which is like a “downtown” of these old temples. Incidentally, Kusado Inari Shrine was built in 807 during the Heian period (794-1185), while Meio-in Temple was founded by Kobo Daishi in 807 (Daido 2). This means that the two shrines were constructed at about the same time. Considering the time of construction, it can be imagined that Meio-in Temple, an old temple of the Daikakuji School of the Shingon sect, was the main construction site.

However, there is no doubt that these two major construction projects were decisive factors in the creation and maintenance of the medieval city of Kusado-Senken. It is certain that all the workers involved in shrine and temple construction were concentrated in this city, creating a “gate market” of sorts. It is obvious that a single major construction project can lead to the establishment of all kinds of industries. It is highly rational to live in close proximity to each other when craftsmen in various related construction fields are working together. The fact that such shrine and temple construction projects have been carried out continuously throughout history seems to have formed the backbone of Japan’s industrial history.

Posted on 12月 21st, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 住宅マーケティング, 日本社会・文化研究 | No Comments »