人間が「住む」ということは、第1に「どこに」であり、「どのように」ということはそれとの関係性において相対的に考えられることがらだと思われる。住宅雑誌を北海道で出版活動してきたのだけれど、この「どこに住むか」というテーマはむしろ従属的に捉えざるを得なかった。それはそのエリア内部での建築の建て方についてが雑誌の主要なテーマであって、その内部での「普遍性」に依拠するから。

ちょうど論議に参加している地域自治体・北海道の住宅施策検討会議などでも、考え方としてはやはり「普遍的なテーマ」に絞り込むのが普通であって、地域選択ということはユーザーの基本的人権にも属する領域なので論じることを一般的には回避する傾向にある。自然ですね。

しかし既存住宅の劇的な改変、性能向上リフォームを住宅市場で活性化させる方策を考えて行けば、そもそもそこに住むユーザーの「居続けたい動機」に注目せざるを得ない。その動機に沿って施策を考えていくことが基本であることは間違いがない。

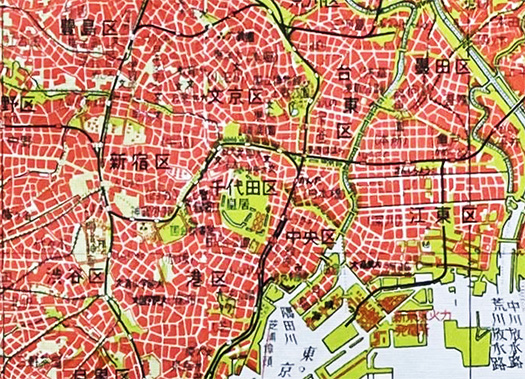

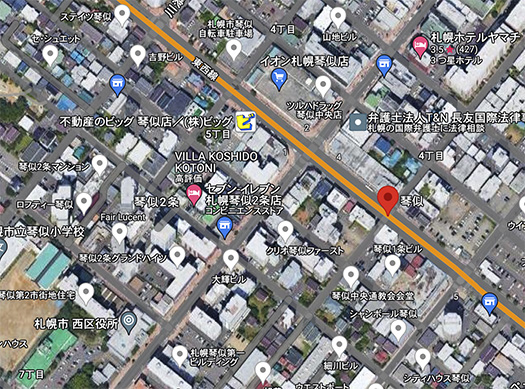

こんなテーマで考えを煮つめ始めて実際の札幌都市内の「エリア」に注目していくと、大きな「バラツキ」が目立ってくるようになる。先日もある要件で市内で10kmほど距離のある地域に移動したけれど、車窓から見える「街並み」に強い「昭和的既視感」を感じてしまっていた。

それはわたしが10代末の頃、運転免許を取り立ての時期。食品製造業の商売をしていた実家の「配達」業務に学生アルバイト勤務していた頃に感覚していた「街の記憶」が甦ってきたのですね。高齢化してきてそういった心情感覚に遊動しがちということはあるけれど、どうもそういう要素を超えている。

いわゆる「街並み」の印象について他との違いというものを感じざるを得なかったのです。行きはひとりだったのだけれど、帰りはカミさんと同道していたので、彼女にも確認したら「そういえばそうだね」とまったく同様の受け止め方をしていた。

そのときふと感じたのは、昭和時代以来、その当該地域は市内の高速道路網からはやや隔絶した地域に属していて、わたし自身も普段はほとんど通行することがなく、相当久しぶりにその道路を走った、という事実。現代では都市はイキモノのように環境状況が流転していく。その変容の最前線からちょっと離れると空気感もそのまま残留し続けるのだと。

やはり同じ都市内でも交通の変化要素が、大きなバラツキを生み出してしまうのだと。

こうしたことは、その地域に住む人のくらしに対して相当の影響を及ぼしていくことだろう。そもそも地域自体が流動性と変化に満ちていれば、そこに住む人の意識も常にリフレッシュされて、時代への対応を自然に考えるのではないだろうか。

建築としての利用要素自体までも変容することが考えられる。

こういうことが大きなヒントになるように思われた。もちろん「では住宅地域としての熟成とは?」という内面からの疑問も浮かんでくる。そういう要素との見合い、兼ね合いのなかで「解」は見いだせるのではないだろうか?

English version⬇

Public and Convenience (2) Mura and Livability – 6

The livability of “villages” in the survival zone changes drastically with changes in transportation convenience. In cities, is the power of metabolism and transformation the power of renewal? Public and Convenience

When people “live”, the first question is “where”, and “how” is considered relatively in relation to the “where”. As a publisher of a housing magazine in Hokkaido, I had to consider the theme of “where to live” rather subordinately. This is because the main theme of the magazine is how to build architecture in the area, and it relies on “universality” within the area.

Even in the housing policy study meetings of local governments in Hokkaido, where I participate in discussions, it is normal to focus on “universal themes,” and since regional selection is an area that belongs to the basic human rights of users, there is a general tendency to avoid discussing it. It is natural.

However, when considering measures to activate the housing market through dramatic modification of existing houses and performance-enhancing remodeling, we have no choice but to focus on the “motive to stay” of the users who live there in the first place. There is no doubt that it is fundamental to consider measures in line with that motivation.

When we begin to think about such a theme and focus on the actual “area” within Sapporo, a large “variation” becomes noticeable. The other day, when I traveled to an area about 10 km away from the city for a certain reason, I felt a strong sense of “Showa-era déjà vu” in the “cityscape” that I saw from the car window.

It was when I was in my late teens and had just obtained my driver’s license. It brought back memories of the town that I had sensed when I was a student working part-time as a delivery driver for my family’s food manufacturing business. Although it is true that people tend to be more emotionally attached to such things as they get older, it seems that I have gone beyond such factors.

I couldn’t help but feel a difference in my impression of the so-called “townscape. I was alone on the way there, but on the way back, I was accompanied by my wife, and when I asked her about it, she said the same thing: “That reminds me of that.

What occurred to me at that time was the fact that since the Showa period (1926-1989), the area in question had been somewhat isolated from the city’s expressway network, and I myself had rarely traveled this road, so it had been quite a while since I had driven there. In the modern age, cities are like a living creature, and their environmental conditions are constantly changing. When you are slightly removed from the forefront of this transformation, the atmosphere of the city remains as it is.

Even within the same city, the changing elements of traffic can create a great deal of variation.

This will have a considerable impact on the lives of the people living in the area. If the region itself is full of fluidity and change, the residents’ awareness will be constantly refreshed and they will naturally think about how to respond to the times.

It is conceivable that even the elements used as architecture itself could be transformed.

This seemed to be a major hint. Of course, the inner question, “Then, what is the maturation of a residential area?” The question “What then is the maturation of a residential area? It may be possible to find a “solution” in the process of considering and combining such factors.

Posted on 2月 19th, 2024 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 住宅マーケティング | No Comments »