昨日、伝統的建造物群保存地域のご紹介をしたので、引き続いて大阪豊中の日本民家集落博物館で見た九州の住宅の事例紹介。さすがに九州はあんまり旅する機会もないので、薩摩の在郷武士の「屯田兵」のモデルとされる住宅群とかくらいで他地域と比較してごく少数。

そんなことから日向、宮崎県ということで興味深く拝見していた次第。

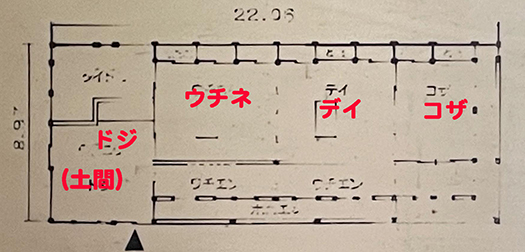

で、この家の由来を見ているとなんと、平家の落ち武者伝承の一族の住宅らしいとのこと。四国では各地で山の中腹などの位置に「隠れ里」のように落ち武者住居が建てられている。そうした場合、山の中腹などの平坦地のごく狭い敷地に建てるものだから、山腹に沿って細長い間取りの家になる。

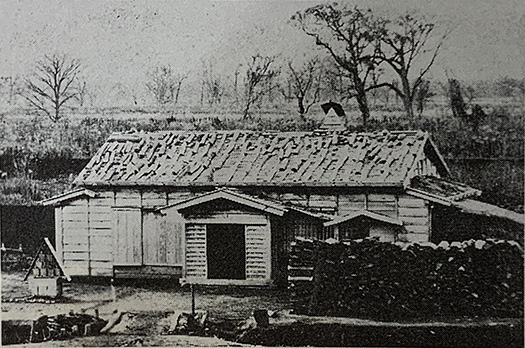

日向でもまったく同様で、日向・椎葉の建築地に建てられていた写真を見るとまんまその通りの立地環境であります。家の後背は山腹に接しているので、窓のない板張りにして湿気や落石から建物を守ろうとしている。こういう知恵で8-900年近い年月を隠れ住んで生き延びてきたということだろう。

よく考えるのだけれど、たとえば今回の能登半島地震で被害を受けた「時国家住宅」も平時国を祖とする落人ということになるけれど、かの家の場合には日本海交易という商業資本として生き残ってきて、幕府側とも折り合いを付けてきたということが想定できる。時国家からは昭和の時代になって宰相・田中角栄を断罪した裁判官も輩出している。歴史の中で生き延びる一族の知恵に深く打たれる。

わたしの想像としては義経が日本海ルートで奥州に逃れ得たのは、このような一族との交渉を表しているのかも知れない。しかし、日向や四国山中などの地域ではどのような「生業」が可能だったのか、成立した幕府体制という軍事暴力至上の強権政治体制の中で、どのように「折り合い」を付けていったのか、興味をそそられる。

ただ、頼朝が全国制圧を仕上げた後、東大寺大仏殿の再建に協力し、その落慶法要に呼ばれて行った際には、超戒厳令のような状況だったとされ、武家政権側としても刺客など「落ち武者勢力」に極度に緊張して対応し、そういうなかで国内和平の「落とし所」を探ってもいたのではないだろうか。

内乱状況が承久の変というカタチで顕在化するに及んで、武力一辺倒ではその後の国内平和維持はおぼつかない。そのように考えて、高く遠い山里に「隠れ住んで」いる連中まで鎮圧することを停止したように思う。

で、落ち武者一族側としても「住めば都」ではないが、南面の大開放の居宅の思いの他のいごこちの良さに充足して、里人との経済圏構築に専念していったのではと推測する。いかがだろうか?

<内部写真含めて,この項あしたに続く>

English version⬇

Minka of the Heike Rakunin in Hyuga Shiiba-1

Exploration of an old private house in Miyazaki Prefecture, the home of a military family that fought in the domestic wars, at an old private house garden in Toyonaka, Osaka. The relationship between the family and the house, which may have suffered a strange fate, is discussed. …

Yesterday, I introduced some examples of houses in Kyushu that I saw at the Museum of Japanese Folk Houses and Villages in Toyonaka, Osaka, following on from my introduction of areas where traditional buildings are preserved. As one would expect, I don’t get a chance to travel much in Kyushu, so I only saw a small number of houses that are said to be models of “Tondabyo” houses built by the local samurai in Satsuma, compared to other areas.

So I was interested to see this house in Hyuga, Miyazaki Prefecture.

I was interested to learn about the origin of this house, and to my surprise, it is said to have been the residence of a family in the tradition of fallen warriors of the Heike clan. In Shikoku, there are many residences of fallen warriors built in the middle of mountains as “hidden villages” in various places. In such cases, the houses are built on a very narrow plot of land on a flat area such as a mountainside, so they have a long and narrow layout along the mountainside.

The same is true in Hyuga, and the photos of the houses built on the building sites in Hyuga and Shiiba show the exact location of the houses. Since the rear of the house borders the mountainside, it is boarded up with no windows to protect the building from humidity and falling rocks. This kind of wisdom must have allowed the house to survive in hiding for nearly 8-900 years.

I often think that, for example, the “Tokikoku Houses” damaged in the Noto Peninsula earthquake were also built by a fallen warrior, who was the ancestor of Taira Tokikoku, but in the case of the Tokikoku family, they survived as a commercial capital trading on the Sea of Japan and were able to come to terms with the shogunate side. The Jikkoku also produced a judge who condemned Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka in the Showa period. I am deeply impressed by the wisdom of a family that survives in history.

In my imagination, the fact that Yoshitsune was able to escape to Oshu by the Sea of Japan route may represent such a negotiation with the clan. However, I am intrigued to know what kind of “livelihood” was possible in areas such as Hyuga and the mountains of Shikoku, and how they “came to terms” with the military violence that was the supreme political power of the shogunate regime that was established.

It is said that Yoritomo was under martial law when he was summoned to the anniversary ceremony of the Great Buddha Hall of Todaiji Temple after he had conquered the whole country.

The civil war that had come to the fore in the form of the Jokyu Incident made it difficult to maintain peace in the country if they relied solely on military force. With this in mind, they stopped trying to suppress those who were “living in hiding” in high and distant mountain villages.

And, as for the fallen warrior clans, although it is not the same as “If you live there, you are in the capital,” I suspect that they were satisfied with the comfort of their large open residences on the south side and devoted themselves to building an economic circle with the villagers. What do you think?

<(See the next section, including interior photos, in the next issue.

Posted on 6月 1st, 2024 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 住宅マーケティング | No Comments »