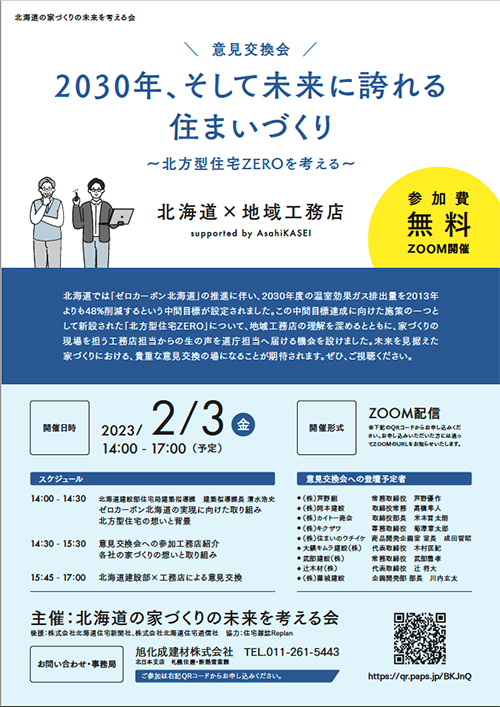

北海道のあらたなゼロカーボン住宅政策である「北方型住宅ZERO」を巡っての広範な世論づくりを目指した行政側・北海道とその住宅施策を体現する地域工務店による意見交換会が昨日行われました。ZOOM視聴での参加総数は150名を超えたという発表。地方自治体行政職員の参加も多数だった。

国の省エネ基準は徐々にレベルアップしてきていますが、地域自治体としての北海道は歴史的にそうした動きを一歩リードする動きを示してきた。ちょうど北欧諸国が断熱先進地として世界の技術開発の先導役を担ってきたことと相似的だった。

ヨーロッパではそうした北欧に対しドイツが近年刺激を受けて「パッシブハウス」という住宅基準を掲げ、世界中にその考えを広めてきた。いまではまるでドイツの方が本場的に有名になっているけれど、そもそもは北欧が起点の動きだった。似たような状況がいま日本でも起きていると言われている。

再生エネのもっとも象徴的な存在としてのPVについて東京都が「義務化」する動きが顕在化。温暖地域の一部からは「北海道パッシング」(もう北海道に学ぶべきことはない)というような意見も出てきていると言われる。とくに最近の断熱オタクという人たちに顕著とのこと。まぁ別にそういう考え自体はあって然るべきだし、そういう自信の醸成は喜ばしい傾向でもあると寒冷地としては考えている。しかしその上で経験交流、深化は本来さらに必要ではないでしょうか?

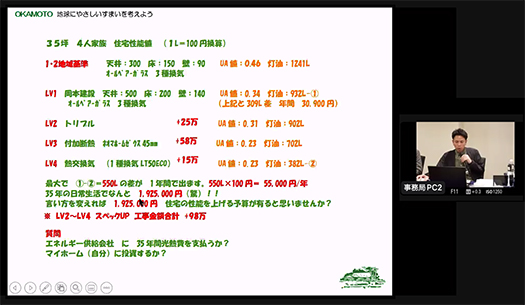

太陽光発電は地域総体の北海道としては一律に効果が高いとは言えない。単純明快な「PV=環境」原理主義的な発想は持ちにくい。同じ北海道でも多雪地域と少雪地域によって大きな条件格差が存在する。そういう条件下で、ゼロエネに資するいろいろな要素を「ポイント化」して10ポイントをもって1トンのCO2削減とみなす北方型住宅ZEROの原案が策定されたところ。

しかしそうした政策ができても実際に取り組む地域の作り手・工務店の意識に浸透していかなければ、どんな施策も効果を十分に発揮できない。道の審議会内部からもまた連携するメーカー企業からも、こうした行政と現場工務店の対話が重要だという認識が高まったことが今回のきっかけ。

むしろ、こういう地域総体の動きが可能であることが「断熱先進地」北海道の最大のパワーであるのかも知れないと気付く次第。ごく一部の事業者や現場を知らない行政の独走ではなく、まさに官民一体となった住宅性能についての施策の現実化が北海道では十分可能なのだと思います。とくに今回は次世代を担う若い作り手のみなさんが参加者の主体。現場感覚に満ちた発言の交換が大きな熱を生み出していた。参加者のみなさんからは「今後ともこういう機会を継続させたい」という発言が一様に飛び出していた。リーダー的な人物が先導する形式よりもはるかに「民主的」な盛り上がりがそこにあった。

Replanとして今回の司会役を編集長の大成彩君が務めさせていただきましたが、こうした民主的な北海道全体のゼロエネへの動きに微力ながらも役立ちたいと思います。

English version⬇

NEWS 2/3 “Hokkaido x Local Construction Companies” Opinion Exchange Meeting

Arousing broad public opinion to promote decarbonized housing policies in the public and private sectors. Maybe democratic power is Hokkaido’s regional strength.

The ZOOM viewer announced that the total number of participants exceeded 150 people. A number of local government administrative officials also participated.

While national energy conservation standards have been gradually raising their level, Hokkaido as a regional municipality has historically shown a step ahead of such trends. This is similar to how the Scandinavian countries have been leading the world in technological development as an advanced insulation region.

In Europe, Germany has recently been inspired by the Scandinavian countries and has been spreading the idea of “passive house” as a housing standard throughout the world. Although Germany is now more famous than Germany, the movement originally originated in Scandinavia. A similar situation is said to be occurring in Japan today.

The Tokyo Metropolitan Government has begun to “mandate” the use of PV as the most symbolic form of renewable energy. Some people in the warmer regions are reported to be calling it “Hokkaido bashing” (there is nothing more to learn from Hokkaido). This is especially true among recent insulation geeks. Well, it is natural to have such a view, and the fostering of such confidence is a welcome trend in a cold region. However, isn’t it necessary to further deepen the exchange of experiences on top of that?

PV power generation is not uniformly effective for Hokkaido as a region as a whole. It is difficult to have a simple, clear-cut “PV = environment” fundamentalist concept. Even within the same Hokkaido region, there are large disparities in conditions between regions with heavy snowfall and those with light snowfall. Under such conditions, a draft proposal has just been formulated for a northern-style house ZERO, in which various factors that contribute to zero-energy consumption are converted into points, and 10 points are regarded as a reduction of 1 ton of CO2 emissions.

However, even if such a policy is established, no measure will be fully effective unless it permeates the consciousness of the local builders and contractors who are actually involved in the project. The recognition of the importance of dialogue between the government and local construction companies, both from within the provincial council and from the manufacturer companies with which it works, was the impetus for this project.

In fact, the fact that this kind of community-wide movement is possible is perhaps the greatest power of Hokkaido, an “advanced insulation area. I believe that it is possible for the public and private sectors to work together to make housing performance measures a reality in Hokkaido, rather than being the sole initiative of a small number of businesses or governments that do not know what is going on in the real world. Especially this time, the participants were mainly young builders who will lead the next generation. The exchange of comments filled with on-the-spot sensibilities generated a great deal of enthusiasm. The participants all expressed their desire to continue such opportunities in the future. There was a much more “democratic” excitement than in a format led by a leader.

As Replan, I would like to contribute to the democratic movement toward zero-energy in Hokkaido as a whole, even if only in a small way, as Aya Oonari, the editor-in-chief, served as the moderator for this event.

Posted on 2月 4th, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 住宅マーケティング, 住宅性能・設備 | No Comments »